April 2021

Ash Yebo

An analysis of the path and arc of the George Floyd Uprising in so-called Tucson, Arizona. This article was originally posted on It’s Going Down.

“What I Saw Was Not Tucson”

– Mayor Regina Romero, the morning after the first riots.

Summer 2020 ignited into the most potent rebellion in a generation. For the purposes of this text, our basic position is that since the summer there has been a massive effort to make us forget. Not least of all is the headlines and congressional hearings proclaiming the January 6th Capitol siege an insurrection: one big show to pretend the summer of 2020 never happened, to give over insurrection as the exclusive realm of crazed conspiracy theorists and white supremacists, and turn our attention elsewhere. Once again, they want to make us fear the power of the crowd, holding themselves up as the arbiters of justice, a justice which for generations has relied on the violence of the police to keep things exactly how they are. Which is to say, intolerable for far too many. So, for them, the summer was peaceful and legitimate, until the “unruly mob” took over. Which is exactly the opposite sequence of events. What follows is an attempt to remember, a recounting of the George Floyd Uprising and the street activity inspired in its wake in the city of Tucson, Arizona.

We Are Together, Kinda, We’re Working on It!

May 29th, 2020

As the rebels in Minneapolis burned down the Third Precinct and the rest of the country watched in awe, friends throughout the Southwest began speculating about what might happen in our region. Graffiti popped up near downtown Tucson citing inspiration from the people of Minneapolis, but the first city to call anything was Phoenix, ninety minutes north. Most of the Southwest doesn’t have a very visible insurrectionary current, despite the history and proximity of the Mexican Revolution and the various indigenous insurgent wars fought in the not-so-distant past.

The first call to action in Tucson was simple – a flyerwith the familiar black and yellow “Black Lives Matter” graphic – for a march the following evening. It was immediately met with skepticism about the legitimacy of its origin: “Were they Black?” “Did they have a legitimate claim to #BlackLivesMatter?,” “Was it a set-up?” If a movement has no leaders, these questions about the identities of the “organizers” are largely irrelevant. What matters is what capacities, potentials and desires exist within the crowd that gathers.

It seemed the people who shouted the loudest on these questions had little interest in attempting to answer them. At best they were distracted by the abstract, perceived ethical considerations some attach to community leadership; at worst they were only interested in calling into question any activity that was not sanctioned by an insular activist subculture. It is dangerous to the spontaneous momentum of a moment to ask such bad faith questions so loudly, especially as activist groups with large platforms and social cred. If anyone wanted to actually find the answers to those questions, all they had to do was pull up the Facebook event page and message the hosts. To anyone who struggled around these questions this summer: You have agency. You have the capacity and judgement to attend any demo with some friends you trust, regardless of the motivations of the people who called it, and either make the best of the situation or walk away if you feel you cannot. You might be surprised at what you find.

When we arrived at Armory Park, we found a strange scene: only about 100 people had gathered, almost all unfamiliar faces covered in pandemic masks, awkwardly keeping distance from each other while clearly excited to be in the world with others again. It seemed most radicals had either fallen prey to cynicism, that “nothing really happens here,” or chose to forsake the moment because the exact identities of the people who called the demo hadn’t been approved of or known by activist leadership. The Sonoran summer was in full swing, with temperatures still well into the triple digits in the early evening. Eventually, two young Black women stood in front of the crowd with a megaphone and said a few words about why they had called the protest. They felt driven to act on behalf of themselves and other Black people who saw themselves in the terrified and pain-stricken face of George Floyd. They said this was the first protest they had ever called, thanked everyone for coming, and we began to march.

As the march snaked through downtown the timid crowd slowly began to find confidence. We cycled through the typical chants, “Whose streets? Our streets!,” signs raised. Nothing seemed altogether different from other marches we had attended here, although there were certainly more Black folks than usual. Black people make up only 5% of the population of Tucson, a fact which some overly concerned with the identities of rioters and protestors fail to concern themselves with. The megaphone was passed among Black people in the crowd – giving them a chance to lead chants, yell instructions to white people, or speak to their frustrations with living Black in America.

Eventually we reached the intersection of Congress and Granada, in front of the Federal Courthouse. Almost every march in Tucson that wants to push boundaries ends up at this intersection, and the cops were fully prepared to shut down the streets and minimize any disruption to traffic. Until then we had seen only a handful of police blocking intersections and following behind the march, keeping their distance. In the evening haze, we heard demands for white people to put their “bodies on the line,” and “white people to the front,” however, the crowd formed a circle, “blocking” an empty intersection with no traffic in sight and no front to move to. Disagreements and frustrations mounted in the crowd as some white allies began to yell instructions at other white people in accordance with what some of the Black folks on the megaphone were saying, but then a different Black person would have completely different ideas as to what white people in the group should do, or whether anyone’s activity should primarily emanate from their social position at all. This confusion and tension slowed the motion and the morale of the crowd, revealing the limits of discourses which often exclusively operate on a level of representation and abstraction. Some people who appeared more prepared for a confrontation started to leave, clearly frustrated at the lack of clarity about what should be done. A couple American flags got burned in the intersection to lackluster applause and the crowd turned back toward the center of downtown.

As the sun went down, we noticed a few louder crews of young people shouting obscenities and challenging the white people in the crowd to do something more than just march. The first confrontation with the police came when a young Black man sat on the hood of a cop car and refused to leave. The crowd surged forward, clearly afraid the cops would arrest the man, but the situation diffused when the cops fled after removing him from the car. The cops were clearly rattled after this and the crowd grew more confident. We started to feel something like our own power. Shortly after, we heard something like “White Lives Matter!” shouted from the Ronstadt Transit Center, to which some young Black folks in the crowd responded by charging the person who shouted, fists flying. The crowd was torn between breaking up the scuffle and wanting to join in. When the two sides separated, someone threw a slice of cake in the racist’s face at which some laughed and moved on.

More active and visible coordination emerged among the crowd. Folks at the front attempted to decide which way to go. “Under the overpass would be easy to kettle, don’t go that way,” and, “There will be more people to see us if we go this way,” could be heard among the discussion. The questions of what white people should and shouldn’t do weighed heavy, which was intimately tied with what was and wasn’t risky for Black people to do. There was clear and palpable disagreement amongst the Black and Brown voices in the crowd as to what role white people should play – some would demand that the white people take a passive role, others would express confusion and dismissal of why any of it mattered in the first place. Much of this seemed devoid of any specific assessment of the situation we were currently in and remained attached to hypotheticals or general assertions based on different conceptions of privilege discourse. All this shifted when a Black woman said on the megaphone, “White people, we know some of y’all have skills to know what to do! Share them with us!” While this more tactical and specific question wasn’t the most repeated, it seemed to significantly shift the group mentality. Now, those elements within the nebulous mass that had a similar impulse could start to find each other, and a rhythm began to cut through the noise. The resonance of one act provoked a, “Yes and…” from another, and the riot that no one thought could happen took form.

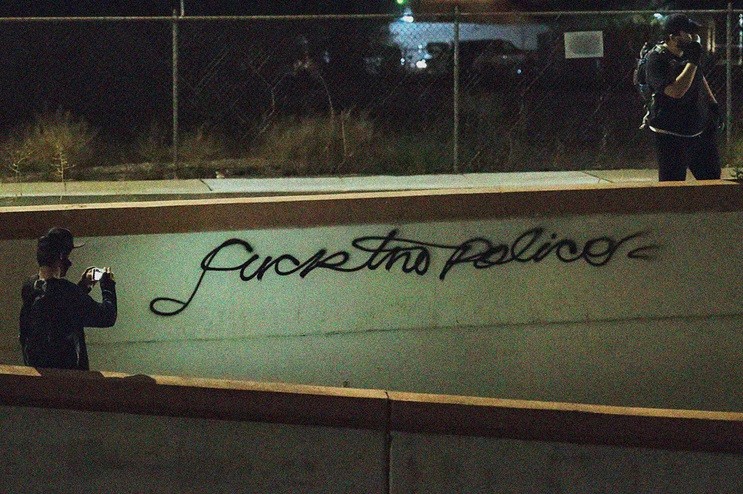

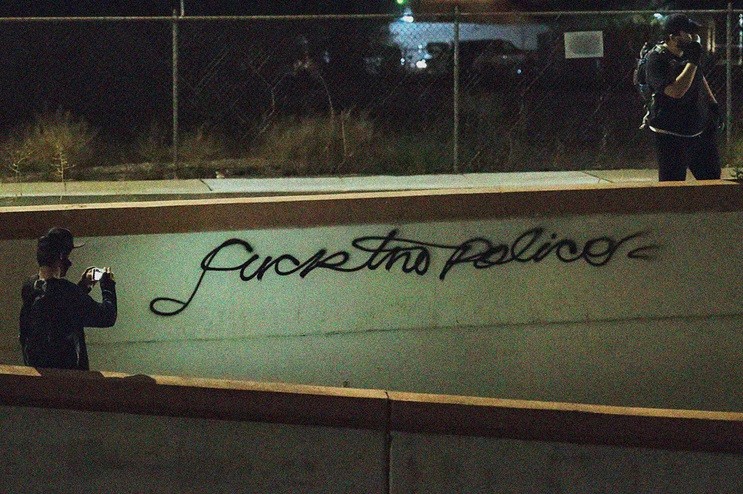

It wasn’t long before a couple rocks went through a window. When the first pane of glass fell it was surprising to hear how much of the crowd cheered. One of the young Black militants shouted, “Let these white people do that shit,” and while most non-white people didn’t seem to hold back, now neither did most of the white people. A large section of the crowd took this moment to go absolutely bonkers. Construction site materials and fencing were dragged into the street to obstruct the police vehicles following behind, countless rocks went through countless windows. Spray paint was handed out and slogans were painted everywhere, on everything. “We are together, kinda, we’re working on it,” “No more waiting 4 now,” and “We won’t stop until we’ve burned this shit down,” was scrawled amidst the flurry of “Fuck 12” and “ACAB” tags. At one point the crowd paused in a side street to decide what direction to go and everything was covered in slogans within 3 minutes. The group couldn’t have been more than 125 people at the absolute peak.

People who had seemingly never even disrupted traffic or moved in this way with a group were attempting to do so, together. There was certainly a learning curve and it was a little comical watching people in the front pull an entire construction fence into the street, effectively cutting the crowd in half. Others would then try to show more effective implementation of the tactic. Being good spirited in these moments was helpful to maintaining momentum and a feeling of cohesiveness. But it’s not rocket science and people catch on rapidly.

The crowd continued through downtown and then north to the 4th Avenue strip, the primary bar and trendy shopping district between downtown and the University of Arizona. “ACAB-19” and “We are going to take back our homes” were tagged on walls along the route. Interestingly enough, the crowd made no attempts to smash or loot any of the businesses there, with the exception of the Sun Tran street car stations. The Sun Tran is a pitiful excuse for public transportation improvement, obviously designed to shuttle and shelter students between the university, the hospital where med students train, the 4th Ave shopping district, downtown, and nowhere else. The pay stations were quickly smashed and George Floyd’s name painted along the way to nowhere.

The first dumpster fire was lit in the intersection of Broadway and Herbert Ave, to much excitement. More American flags burned in the fire and “Black Lives Matter, Fuck the Cops” was spray painted on the side of the dumpster. This first set of dumpster fires set off an obsession amongst the crowd, as every dumpster found in its path for the rest of the night became a flaming barricade in the closest intersection. The Arizona chain coffee shop, Cartel, got smashed up, while Thunder Canyon Brewery next door was spared. The people doing the smashing were heard multiple times discussing which targets were appropriate, and Thunder Canyon has hosted fundraisers and events for community-based groups, perhaps winning them a reputation further than they realize. This may not have spared other businesses with good intentions, but reputation certainly can be a factor.

The first few arrests of the night came when the crowd re-entered Armory Park to regroup. Numbers had thinned a bit and the cops seemed to take this opportunity to pull cars over and arrest people for helping hold the street in the back of the group. The group moved to the downtown police headquarters which had become an instinctive gathering point in almost every city after the burning of the Third Precinct. There couldn’t have been more than seventy-five people, but as the images of burning dumpsters, graffiti, and smashed windows spread rapidly across social media, new people gravitated towards the downtown precinct looking for the action.

This was the first time that the police formed a line in riot gear, but not before the facade of the station was covered in “Viva la Raza,” “Fuck 12,” and “ACAB” tags. As new faces gathered in front of the riot line, holding their hands up and yelling at the officers, livelier activities accumulated in the back, closer to the dimly lit streets of Barrio Viejo. Young people drove slowly through the intersection, blasting NWA and Nipsey Hussle, hanging out the windows and shouting. The crowd swelled to around 300-400 people at the peak of the standoff at the precinct. Occasionally, a water bottle or rock was lobbed from this area at the riot line, and people in the front shouted for people to stop. This was the first time any significant shouts of “No violence!” could be heard, with seemingly no concept of the irony that their presence was precisely because people burned dumpsters and smashed windows. Policing doesn’t just manifest in riot shields, batons, and bullets, but in the heads of every citizen.

This was also around the time the first fight broke out within the crowd of demonstrators. Confrontations with journalists flared further splits over tactics within the crowd and some of the rowdier elements were expelled or left for fear of being targeted. Ironically enough, while the insistence on non-confrontation with the cops was often justified through the claim of “protecting” the most vulnerable, many of these crews were Black and brown. The party continued in the back for quite a while despite this, but a line had certainly been drawn by the activists that few felt empowered to cross. For the rest of the night, incursions by the police were met with bottles and rocks from the back, and the throwers were shouted down by the activists ever-worried about violence. A one-sided concern to be sure. Eventually numbers dwindled and the night ended in a sputter.

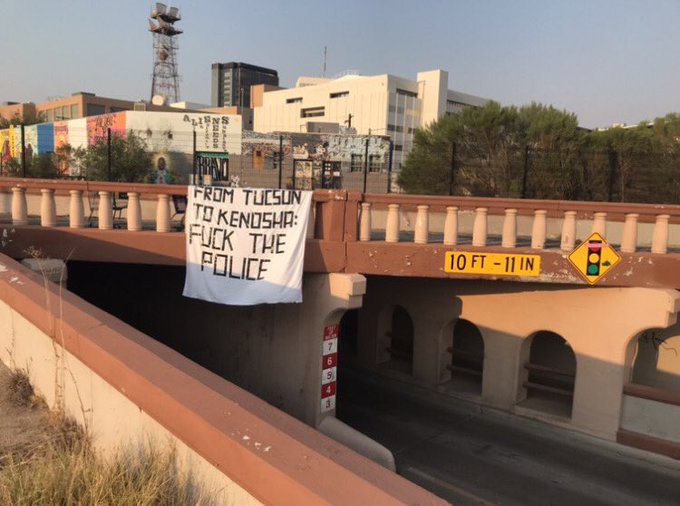

It is worth honorably mentioning that we caught wind of a banner drop and multiple large ACAB tags which appeared far outside downtown during the night. These acts took place occasionally throughout the first week, even during the curfew. This showed an encouraging spark of creativity and an attempt to engage the terrain outside of the militarized zone that engulfed downtown.

The Battle of 7th Street

May 30th, 2020

After the ruckus the night before, you couldn’t go anywhere without hearing about it. A speak-out on the university campus was canceled, city officials stood with the police chief to condemn the murder of George Floyd and also the violence of the demonstrators. The local news was full of reports surveying the damage and the controversy. This familiar story played out across the country. Clips of Black “leadership” claiming the rioters weren’t Black were juxtaposed with clips of Black rebels rioting in the background.

As night grew closer, people gathered at the University of Arizona despite the official event getting canceled. There was too much momentum for any self-appointed organizer to cancel anything. Now a crowd of around 700-800 people marched their way between the university and downtown. This crowd went relatively unencumbered by police for a couple hours, despite graffiti crews leaving a trail of tags, slogans, and the rich smell of spray paint in their wake. The march circled back to the campus to have a speak out under the buzz of helicopters. Riot police assembled downtown and it was obvious the scenario was going to play out much differently from the night before. After a long speak out from predominantly Black students ended, the crowd began to move again. About 300 people made their way back toward downtown, but were immediately met with a riot line at the underpass entering downtown. This became the primary dynamic of the night.

Downtown Tucson is cut off from the entirety of the north side of the city by train tracks that run east to west across the northern boundary of downtown. All the main roads and sidewalks flow underground through multiple underpasses to enter downtown. The group’s obsession with going to the downtown police station became the primary limitation on the activity of the night. Marches split up and converged multiple times through the evening, attempting to find a way around the police lines easily blocking the underpasses. Sometimes small groups would light fires in the street or attack businesses along the way, but rarely did this serve much material purpose beside catharsis. No new opportunities were opened up by these acts because the vast majority of people on the streets still saw it as the goal to reach downtown. The crowds didn’t feel brave enough to attempt to break the police lines, likely in part because the police clearly had the tactical advantage. Their lines were formed up the hill with the crowd trapped in the underpass. This changed at the battle of 7th Street.

The one place that traffic is not forced underground to get into downtown is where 7th Street and 7th Ave converge. This low traffic intersection feeds across the tracks at ground level into downtown, intersecting shortly afterwards at Toole Avenue. Once again, the demonstrators converged on this point, headed off by only a small and weak riot line of police. This was a decisive moment of the night because as the crowd attempted to move across the tracks, an approaching train was heard and the crowd hesitated. Suddenly, mobile units of uniformed Arizona State Patrol officers pulled up to the crowd on 7th Ave, jumping out of unmarked SUVs and pelting the crowd with pepper balls. This pushed the crowd back up 7th Street, going east. This was our first encounter with these units. They would be the primary force to deploy chemical weapons for the rest of the summer. So begins the battle of 7th Street.

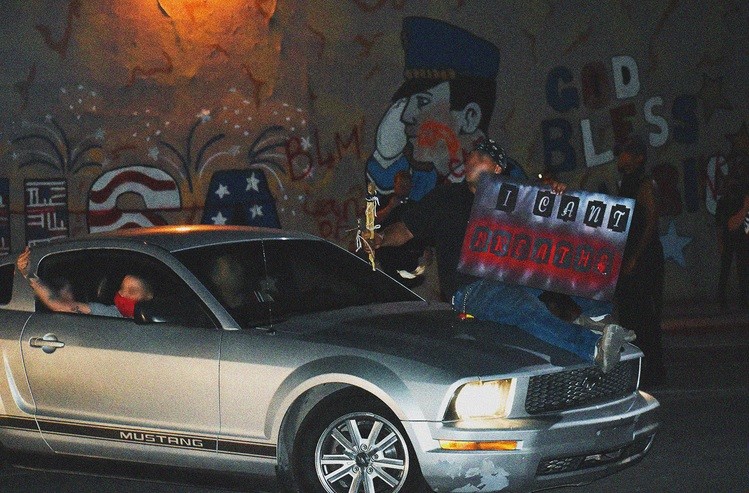

The primary clashes of the night took place along 7th Street between 7th Ave and 5th Ave. Occasionally, small groups broke off and attempted to find another way around, but there was no feasible path for any more than a handful of people to cross the tracks without meeting riot cops. A similar scene as the night before played out at the intersection of 6th Ave and 7th Street. At the front, activists held their hands up and pled with police, while the people looking for something more interesting to do hung in the back, partying out of cars and covering the patriotic mural on the side of Miller’s Military Surplus in graffiti. Occasionally a rock or bottle was thrown from the back, only to be shouted at by people in the front. There seemed to be an obvious split this time between students (often in the front, Black and white, stickers on their water bottles, camelback packs on their backs) and the more heterogenous grouping of people in the back. This party element was more multiracial and read as more “subcultural.” Cholos would slow roll in their cars blasting music while hardcore kids, punks, graffiti writers, and street youth roamed about looking for materials to start fires and windows to break. Often those in the front wore nothing but cloth covid masks and tank tops, while those in the back donned t-shirt masks, athletic wear, or a combo of bandanas, hoods, and hats.

This long standoff, with occasional clashes and incursions from the cops, played out for what felt like a few hours. Our crew walked off to take a break and see what else might be happening in the area. As we wandered back, we heard a couple gun shots and observed a portion of the crowd fleeing east down 7th Street. When we got closer, we could see an SUV swerve through a cloud of dust, the crowd splitting to let it through. The driver was waving a handgun around and it was unclear at first whether he was firing into the crowd or at the police. This was a jarring moment as he let off more shots in the direction of the riot line and sped off. As plenty of friends have observed, the presence of firearms can play decisive roles in these situations. The tactics we choose to employ in a moment can be what tips the scales in one direction or the other, they can make a crowd feel powerful or completely disempowered. This moment seemed to do both.

People had been in the streets, in over 100-degree heat, since the afternoon. Throughout the summer this factor cannot be overstated. It was exhausting. This, combined with being repeatedly unable to reach downtown while also refusing to direct energy anywhere else resulted in a collective exhaustion that, for a lot of people, seemed to reach its end point after the erratic gunman in a car wildly shot at the cops. A sizable portion of the already-demoralized crowd was now afraid of getting shot. A smaller portion of the crowd stuck around, adrenaline pumping, sweaty, and wild eyed. The police, likely also full of adrenaline at this point, made a push for the crowd to move further east down 7th Street. This was the first whiff of tear gas of the long summer. In response, the determined group of rebels quickly lit a dumpster fire next to Miller’s and used nearby construction equipment to build a barricade further down the block. Traffic signs became shields against pepper balls, and rocks were pelted at the cops at regular intervals. The activists had all gone home after the gun shots, but so had many others. There couldn’t have been more than fifty people left, facing off with over 100 riot police, a helicopter, and snipers on downtown roof tops pointing at people from hundreds of yards away. This clash went on for almost an hour, until finally the mobile units in SUVs flanked the small crowd from behind, released multiple canisters of tear gas at once, and attempted to snatch multiple people, scattering the crowd and ending the night. Remarkably, some people were de-arrested and at least one SUV got its window smashed in the melee.

Counter-Insurgency 101

June 1st, 2020

In a fairly typical act out of the counter-insurgency handbook, organizations associated with the City of Tucson government quickly announced a vigil, to be held at the Dunbar Springs Pavilion. It coincided with the first night of the city-wide curfew that started at 8pm. Dunbar Springs, just north of downtown, is one of two historically Black neighborhoods in the city. The neighborhood has been thoroughly gentrified over the last twenty years and few remnants of the old neighborhood remain. This was the first time we saw a crowd of this size, close to a thousand. Many local Black activists vocally opposed the vigil, as it was clear to anyone paying more than a few seconds of attention that it was an effort to co-opt and pacify the rage and anger sweeping across the country. The attendees overflowed the pavilion and into the street. There were certainly people of all ages present, but this was by far the whitest and the most docile. Various spokespeople gave speeches, pleading for peace and invoking Martin Luther King, Jr. The vigil ended by reading the names of Black people killed by the police. Many of our friends moved to the front, as we had been told a group of queer Black people would attempt to take the stage. As some young folks stood on the stage and shouted, it was demoralizing to see how few in the thinning crowd seemed to even notice that something was happening. A few hundred people stuck around, largely young, and shouted, “Let them speak!” Speeches were attempted but largely went unheard, as the men who seemed in charge of the official event refused to allow the younger group to use the mic.

Not long after, closer to the university, a small group attempted to march and defy the curfew, but they were quickly broken up and twelve people were arrested. We didn’t know it at the time, but this would signal the end of the revolt itself in Tucson. The curfew and the activists had demoralized the uprising enough to crush it. However, there was an explosion of energy and activity in the city that would last most of the summer, the high points of which we will attempt to highlight below.

The Activist Turn

June 6th, 2020

For the next couple months there would be a march, protest, or other political/activist event once a week or more, which is unusual for Tucson in recent years. It would be impossible and honestly boring to mention every event that took place over the summer. While many of the events resulted in new people finding each other, many of them were small and exhausting. The local chapter of Black Lives Matter hosted a Celebration of Black Lives on the University of Arizona campus after initially announcing they wouldn’t be planning any public events. The hours-long event brought together poets, activists, students, and musicians to perform and speak to a crowd of thousands. The temperature was in the upper nineties–relatively cool compared to the rest of the summer.

As the event wrapped up and some of the thousands began to disperse, chanting swept through the crowd as a march stepped off campus and took the familiar route towards downtown. This was the biggest march all summer. It snaked towards downtown and through the West University neighborhood, numbering around 1,200 people. The group paused near the intersection of Stone Ave and 6th Street, debating whether to go downtown or try something new. This time, some contingents in the crowd had come much more prepared. After some debate, the crowd began marching toward the westside down 6th Street, and a mobile sound system made its way to the front of the march. People made requests and got excited, some dancing and many laughing. The energy built in the crowd as we passed under the I-10 overpass, taking a left south towards the on ramp. It was clear that the intent was to take the highway, and the crowd started moving faster with excitement. There were very few cops in sight. The t-shirt masks came out and “Black Lives Matter,” “Fuck 12,” and “ACAB,” appeared in spray paint on walls. We danced around prickly pear cactuses and landscaped ocotillos, and cheered as the first people climbed onto the highway with only a few State Patrol cars to meet them.

Strangely, when those on the highway looked back, very few of the crowd had followed. Appeals were made to join the group on the highway. Some demanded white people put their bodies on the line, some insisted there were no cops, some said, “safety in numbers.” No appeal seemed to work. This collective hesitation once again allowed the State Patrol–this time the highway division–to amass more numbers on the highway. These seemed to be the same units encountered back on May 30th by the train tracks. Some of the vehicles were unmarked and they quickly deployed pepper balls at a few people on the highway. At least one protestor responded by attempting to break the window of a patrol car. Then the State Patrol let off a smoke bomb, which seemed to startle the already-timid crowd below. Many demonstrators scattered into the wash of the Santa Cruz River. The police also seemed erratic and unprepared: we witnessed an officer jump out of his vehicle with no helmet, wildly attempting to fire bean bag rounds at those facing off with him, not realizing his safety was on. The protestors took this opportunity to heckle him mercilessly, of course.

As our numbers depleted and we realized there was no good way of pushing all the way onto the highway, the crowd continued south to attempt to go under the highway and into downtown. By this time, a riot line had formed and the crowd didn’t seem brave enough to make the push past them. At every turn, the timidity of the crowds allowed the disorganized and uncoordinated police to amass their numbers. There was a prolonged standoff under the highway overpass, but eventually we turned back as the number of demonstrators had dwindled to less than 150. What was left of the march made its way back to the university with no arrests, the wildfire on Mt Lemmon glowing in the dark as an apocalyptic reminder of the stakes of our times.

Nana Ayúdame

June 25th, 2020

Carlos Adrian Ingram Lopez was murdered while being restrained in police custody, in front of his grandmother in the early hours of April 21st, 2020. Crying out to her in his final moments, Carlos yelled repeatedly “Nana Ayúdame” (“Nana, help me”), which became a rallying cry and chant for the rest of the summer. The body cam footage was eventually released to the public and it is truly horrifying. A full account of the tragedy, and what the family and their friends have done in response, is not within the scope of this piece. What feels most relevant to understanding the dynamics of street activity in Tucson for the summer is the night of the vigil that his family and supporters called for on June 25th.

When news broke about the police keeping an in-custody death from the public for two months, it was a scandal. The Tucson Police Department prides itself on its progressive image. When the rebellion broke out in Minneapolis, much of the local reaction from the City and TPD included claims that the problems that exist in other police departments do not exist in Tucson. The murder of Carlos called all of this into question in a very public way.

The vigil was called in the evening by Carlos’ family and a coalition of multiple activist organizations in the city. About 500 people assembled at El Tiradito, a public shrine just a few blocks from the downtown police headquarters. After hearing speeches and testimony from the family and various organizations, banners appeared at the end of the block and, using a mobile sound system to rally people, a march began towards the police station. When it reached the station, people who had experienced police harassment and violence or had lost someone they loved to the cops were given the chance to speak. A small line of police stood back from the sidewalk, careful not to appear hostile. These officers didn’t have full riot gear on, but we could easily see a mass of riot cops assembled just inside the lobby of the station.

The energy was unsurprisingly tense and much of the rhetoric was hostile and aggressive. It felt like something could happen. Three banners were at the front, creating a visual buffer between the police and demonstrators, while people that wanted to speak often stepped in front of the banners to yell at the police or speak to the crowd. When some organizers wanted to march back to El Tiradito, much of the crowd stayed, including some of the family. It seemed clear that some in the crowd wanted a confrontation, to bring into reality the conflict that is often hidden and one-sided in everyday life. We’ve racked our brains for months about what could have pushed the night over the edge, but we still aren’t sure. Eventually the crowd dispersed and went home.

The Highway, Revisited

July 22nd, 2020

From this point on the crowds became increasingly small, but remained spirited. They were also increasingly exposed to arrests and police harassment. Many of the remaining charges (aside from the curfew violations) are from this period, as many charges from the first weekend have been dismissed or settled for fines and community service. A new, direct action-oriented group–made of a multiracial crew of Zoomers, some of whom were still in high school–emerged. They are one of only a couple crews that visibly remain in the streets after the summer, but we are confident plenty more have found each other and are building their capacity for other interesting things. As some evidence of this, we’ve seen new-but-familiar faces at mutual aid programs and tenant organizing throughout the city.

The final flash point in the streets came during one of these smaller marches. Each march was around 50-100 people, depending on how much traction it had gotten on social media. They were relatively consistent in their composition and accepting of tactics that just months ago would have been considered “violent.” It was exciting to see this combativeness in Tucson, albeit with a strange set of ever-changing limitations on what was acceptable. Often graffiti was ok, and even cheered, while dragging debris into the streets to obstruct traffic was only sometimes acceptable. People called themselves “organizers” while saying they couldn’t control what people did and then they’d turn around and stop someone from pulling a newspaper box into the street. Other times we could see the same people join in to have some fun. These anecdotes don’t seem unique to Tucson and are a testament to the new potentials that emerge in a rupture. New elements are always confusing to the radicals and liberals alike, and always adapting to new conceptions of what is both acceptable and possible.

One particularly spirited march attempted to make its way to an on-ramp as night fell, but the police were far more prepared for these smaller marches and had prioritized the highway and more brutal measures for groups they perceived as more combative. When the small crowd of about fifty stepped onto the ramp, tagging walls along the way, the Highway Patrol was already lined up with their cars blocking the way. Some in the front of the crowd sat down and locked arms, and the typical unlawful assembly announcement could be heard over a loudspeaker. Some shouted at the police and pulled out umbrellas, prepared for what was

obviously about to happen.

It didn’t take long for the first smoke to get launched from the cop’s side and the nonviolent resisters immediately retreated behind the line of umbrellas. The black bloc as a uniform was never heavily present in Tucson, likely on account of it being 110 degrees almost every day, but t-shirt masks, goggles, hat/sunglasses/surgical masks, and umbrellas were a regular fixture of the more combative demos, especially towards the end. This proved useful in this moment, as these elements in the demo now made up the frontline organically, as they were ready to resist the police weapons more than others. The small crowd held its ground fairly well, even after a couple tear gas canisters were kicked back and the crowd was pelted with pepper balls. Luckily for us, the wind was at our backs, blowing much of the toxic gas away from us. We slowly backed away, keeping together and providing cover for a few people who needed to be treated by the medics. Unfortunately, the crowd was small and still in a defensive posture, completely out in the open between the raised highway with the dry Santa Cruz River at our backs. There wasn’t much to do but slowly retreat, attempting to keep the crowd together. As we marched back, one of the few rains of the summer came down. A feeling of relief swept through the march and people danced and chanted for the rain and for the power everyone felt, however small. The march dispersed into the night shortly after.

Whose Land? O’odham Land!

Including the struggle against the border wall near Ajo, Arizona may seem like a strange choice in an article about the George Floyd Uprising. A full account of the blockades, scuffles, and demonstrations against the border and in defense of indigenous sacred sites is not our intention, nor our story to tell. However, we think it is vital to place the clashes that occurred in the West Desert alongside the clashes in the streets of Tucson because, the fact is, one directly fed into the other. When the Kumeyaay people in California began their encampment against the wall on their territories, it was a call heard throughout the region. O’odham people in Southern Arizona have been resisting the border for generations, but there were more than just wildfires and a virus spreading throughout the Southwest in the long, hot summer of 2020.

When the O’odham put out the call for support, a huge portion of the people who responded were those who had found each other in the streets of Tucson and Phoenix earlier in the summer. These newer crews came together with other networks of Indigenous people, environmentalists, humanitarian aid workers, immigrant rights activists, and other residents of the border region to physically push against border wall construction near a sacred site known as Quitobaquito Springs. Multiple weekly actions slowly escalated, shutting down wall construction at a variety of points, as well as a Border Patrol checkpoint. There was also a large solidarity demonstration in Tucson of over 100 people.

Tactics and gestures from earlier in the summer manifested in a completely different geography on O’odham land. Construction material from the wall was used to slow the advance of Park Ranger and Border Patrol vehicles. Medic crews who had organized in the cities now drove two-and-a-half hours to disperse water and flush eyes in the middle of the desert. Cliques of friends who learned to face off with police lines de-arrested their comrades repeatedly amongst thorny desert vegetation. Umbrellas became sunshades and tear gas was kicked back at the State Patrol. This level of activity was impressive because of the vast geographic area in which it took place, in the heat of the day, some actions lasting eight hours. Shortly after the Border Patrol checkpoint was shut down and several people were brutally arrested, the momentum of the movement died. Likely some people began to put their hope in the election cycle, but the biggest factors seemed to be practical and logistic. Many of the limitations of the Uprising had the volume cranked up in these clashes, both because of geography and the increased atmosphere of repression that was by then sweeping across the country. A lingering paranoia and resentment that can be traced back to the repression, trauma and internal dynamics at Standing Rock were also ever-present.

The most immediate, material hurdle on the side of partisans in the battles against the border wall in August, September, and October was the lack of any hub or base of operations in the area in which actions were taking place. We understand there are many factors in this, namely a lack of resources and cultural and legal obstacles around welcoming outsiders onto the reservation or other tribal lands. An exploration of those dynamics and possible solutions cannot be done here, but the fact remains that having no place for people to convene together, to talk, plan and build relationships beyond text loops and combative clashes with the authorities, severely hindered many people’s ability to participate and sustain the struggle. To illustrate this profound material and logistical limitation geographically: the largest town close to Quitobaquito Springs is Ajo, Arizona, about forty-five minutes away. Ajo is south of two Border Patrol checkpoints and roughly two-and-a-half hours from either Tucson or Phoenix. Making this trip weekly, especially when few people from the cities knew anyone in Ajo or other towns to stay with, is extremely taxing on resources and stamina. Many of the actions began at the start of the work day, which often meant camping in a National Park the night before or leaving the city at three or four am to arrive with enough time to get our bearings and converge with the others. Attempting to solve this problem collectively, a couple vehicles were eventually acquired and put at the disposal of some of the O’odham land defenders, but it wasn’t enough for the struggle as a whole. Those of us committed to seeing the end of this world and the subsequent birth of whole new ones cannot accomplish this on sheer determination alone. We must build our capacities to both live and to fight.

Over, Not the End

We are left wondering what a more coordinated and confident cluster of friends could have accomplished in some of these moments. We don’t like to think of ourselves (or others interested in revolutionary ideas) as any sort of separated and determined vanguard above the crowd, but we do think our aspirations and experiences can offer a relatively unique approach and preparedness to the situation. In the best moments, when put at the disposal of a struggle, these capacities can help keep the situation open longer and temporarily sideline the counter-insurgent forces that always emerge. If our friends and comrades had been more prepared, not just materially but strategically, mentally, collectively, even spiritually, could we have had the confidence to intervene in these struggles over tactics and strategy more effectively? The baggage of ally-based political frameworks seemed to routinely sideline even those of us with strong disdain for such political discourse, making us fearful of interventions that could expose us as agitators to an at-times hostile crowd. This doesn’t just effect those coded as white. This also doesn’t remove questions of social position from the equation. Racialized people in the crowd, both insurgents we did and didn’t know, seemed to lack confidence to intervene in these situations. Those who did were singled out. What could have been done to disable these counter-insurgent impulses? We must attempt to assess as many of the forces on the ground, both the material and immaterial, as best we can in the moment to be able to ask, “What is possible in this moment” and then the logical follow up, “How is it to be done?” If we see ourselves as part of the crowd, an element within it which brings to bare insights, capacities, and knowledge, we must be willing to add to the crescendo of forces at play in the moment. When we separate ourselves from the situation, whether on the basis of social position (who gets to take initiative based on perceived identity) or ideology (“normal” people vs radicals), we rob ourselves and the crowd of the lessons and informed strategies we can bring to the table. We must not strip ourselves of a responsibility to the situation in which the horizon of what seems possible is wide open.

To think together takes time. This means developing an understanding of each other and our context, not just an affinity for a similar lexicon, subculture, or ideology. This can sound elementary to those of us who have been in it for some years now, but it’s surprisingly easy to forget how much talking and thinking together, both formal and informal, is necessary to act swiftly and confidently in the heat of a moment. We must, of course, acknowledge that the pandemic and the anxieties around spreading it that proliferated in radical milieus in Arizona at the time hindered greatly our ability to be together and have these conversations, mixed with a heat that made it nearly impossible to hold larger group conversations outside.

We also think it’s important to remember that, debatably, much of our activity was outside of what much of the anarchist and broader radical milieu in Tucson has occupied itself with for the last several years. Our presence in the streets in the first days in and of itself was not the norm, and this weighed heavily into who began talking and coordinating together since then. Forming these levels of trust and coordination quickly with no prior experience together is hard, and overall our friends rose to the occasion. We are now stronger and more confident for it. Hindsight is always 20/20, so it’s easy to see what look like mistakes, but at the time we were working with what we had in an unpredictable and chaotic situation. In that spirit, there are a few proposals we might put forth for groups of friends to consider as these emergent rebellions are likely to continue. We are living at the end of America. We are just getting started.

1) Communications: Take better stock of communications infrastructure at the disposal of the emergent movement. A Telegram channel was established after the first couple weeks of activity that seemed very effective for distributing on the ground, by the minute info to participants in the street. Flyers were distributed both at marches and on social media accounts. But administrating something like this consistently takes a lot of work. Were there established social media accounts or other platforms with large and diverse followings that could have been utilized more effectively? We must think beyond the radical and activist milieus, especially since they were clearly not present in the first few days.

2) Coordination amongst experienced crews: Some of this absolutely occurred, but we could have gone further, particularly in the midst of the crowds themselves. We could have been more pro-active at demonstrating new and effective tactics to people who were beginning to act in more direct ways. This could look like crews at the back trying to cover the rear, talking to people about covering identifying features, changing clothing, being vocal about why people might be deploying particular tactics in a given moment. Another pair or two could be at the front trying to communicate about pace or helping read police formations. Some folks carried extra goggles, masks, pamphlets and other supplies to hand out, but most of this occurred after the first few nights when a lot of the combative energy had already been drained. We also must expect that others in the crowd are coming with their own plans which may be better than our own. We should be on the lookout for these folks and not be afraid to talk to them. We can then possibly be more prepared for spontaneous, swarm-style tactics. We saw evidence of this by the second night of the riots, when people appeared in Frontliner-style gear, with spray paint and goggles, often sharing spare supplies. The mobile sound-system one group of people brought a couple weeks in was highly effective at keeping energy up in the crowd and made it easy to signal to other people where the party was.

3) Generate new and inventive slogans: Others have articulated this already in regards to the yellow vests in France, but we could have put this into better practice in Tucson. “Be Water, Spread Fire” and “Welcome Back to the World” come to mind from Minneapolis, or the famous writing on the QuikTrip gas pump in Ferguson placing the riots in 2014 in a continuum with Spain in ’36, Watts in ’65, and LA in ’92 among others. The graffiti that appeared near downtown before the first demo added to an atmosphere that something was about to happen. There was graffiti mocking the curfew, “Oh no! I’m out after 8!” seen around 6th street. Graffiti, flyers, banners, and creative chants could have added to broader conversations in the movement in ways we couldn’t immediately expect. There was some beautiful graffiti the first couple of nights, some of which made it on to the local news. What slogans could we imagine on the nightly news that could speak to people regardless of the tone of the coverage in which it appeared?

4) Autonomous Demos and when to call them: If you’re going to call a demo, call it early. The tension among our cluster all summer was about calling autonomous actions. We never had a consistent, shared understanding of the situation and what we could achieve in it together. There are many reasons for this but, regardless, the end result was that some of us felt our initiative had been dampened and others felt concerned that we would just be burning ourselves out trying to bring increasingly smaller numbers into the streets. If some of us wanted to assert the legitimacy of autonomous street activity, we could have jumped on it sooner rather than later. This way, even if it was small, it would be happening amidst a wave of broader activity, adding to the array of forces rather than being isolated. In hindsight and with more capacity, something called in the very first week may have been very interesting.

5) Experiment with other forms of gathering: Demos aren’t the only events that needed to happen in the midst of a pandemic. Could the tensions from point 4 have been settled more easily if they had moved away from the demo as the primary form that was imagined? Eventually, an autonomous march was called and was well attended. However, by this point the police were beginning to show up in overwhelming force. Some attendees proposed that the gathering didn’t have to be a march, it could be anything the crowd wanted to do together. An assembly became a march became a speak out became a dance party. The overwhelmingly positive reception was evidence that we should have probably tried this much sooner, with the one caveat being the branding or coding on the flyers. Keeping the description vague and emphasizing the agency and desires of those attending would have left the situation even more open, allowing us more room to experiment with different ways of being together than the typical activist gestures that many inevitably default to. And be careful about who gets to hold the megaphone…

April 2021

Ash Yebo

An analysis of the path and arc of the George Floyd Uprising in so-called Tucson, Arizona. This article was originally posted on It’s Going Down.

“What I Saw Was Not Tucson”

– Mayor Regina Romero, the morning after the first riots.

Summer 2020 ignited into the most potent rebellion in a generation. For the purposes of this text, our basic position is that since the summer there has been a massive effort to make us forget. Not least of all is the headlines and congressional hearings proclaiming the January 6th Capitol siege an insurrection: one big show to pretend the summer of 2020 never happened, to give over insurrection as the exclusive realm of crazed conspiracy theorists and white supremacists, and turn our attention elsewhere. Once again, they want to make us fear the power of the crowd, holding themselves up as the arbiters of justice, a justice which for generations has relied on the violence of the police to keep things exactly how they are. Which is to say, intolerable for far too many. So, for them, the summer was peaceful and legitimate, until the “unruly mob” took over. Which is exactly the opposite sequence of events. What follows is an attempt to remember, a recounting of the George Floyd Uprising and the street activity inspired in its wake in the city of Tucson, Arizona.

We Are Together, Kinda, We’re Working on It!

May 29th, 2020

As the rebels in Minneapolis burned down the Third Precinct and the rest of the country watched in awe, friends throughout the Southwest began speculating about what might happen in our region. Graffiti popped up near downtown Tucson citing inspiration from the people of Minneapolis, but the first city to call anything was Phoenix, ninety minutes north. Most of the Southwest doesn’t have a very visible insurrectionary current, despite the history and proximity of the Mexican Revolution and the various indigenous insurgent wars fought in the not-so-distant past.

The first call to action in Tucson was simple – a flyerwith the familiar black and yellow “Black Lives Matter” graphic – for a march the following evening. It was immediately met with skepticism about the legitimacy of its origin: “Were they Black?” “Did they have a legitimate claim to #BlackLivesMatter?,” “Was it a set-up?” If a movement has no leaders, these questions about the identities of the “organizers” are largely irrelevant. What matters is what capacities, potentials and desires exist within the crowd that gathers.

It seemed the people who shouted the loudest on these questions had little interest in attempting to answer them. At best they were distracted by the abstract, perceived ethical considerations some attach to community leadership; at worst they were only interested in calling into question any activity that was not sanctioned by an insular activist subculture. It is dangerous to the spontaneous momentum of a moment to ask such bad faith questions so loudly, especially as activist groups with large platforms and social cred. If anyone wanted to actually find the answers to those questions, all they had to do was pull up the Facebook event page and message the hosts. To anyone who struggled around these questions this summer: You have agency. You have the capacity and judgement to attend any demo with some friends you trust, regardless of the motivations of the people who called it, and either make the best of the situation or walk away if you feel you cannot. You might be surprised at what you find.

When we arrived at Armory Park, we found a strange scene: only about 100 people had gathered, almost all unfamiliar faces covered in pandemic masks, awkwardly keeping distance from each other while clearly excited to be in the world with others again. It seemed most radicals had either fallen prey to cynicism, that “nothing really happens here,” or chose to forsake the moment because the exact identities of the people who called the demo hadn’t been approved of or known by activist leadership. The Sonoran summer was in full swing, with temperatures still well into the triple digits in the early evening. Eventually, two young Black women stood in front of the crowd with a megaphone and said a few words about why they had called the protest. They felt driven to act on behalf of themselves and other Black people who saw themselves in the terrified and pain-stricken face of George Floyd. They said this was the first protest they had ever called, thanked everyone for coming, and we began to march.

As the march snaked through downtown the timid crowd slowly began to find confidence. We cycled through the typical chants, “Whose streets? Our streets!,” signs raised. Nothing seemed altogether different from other marches we had attended here, although there were certainly more Black folks than usual. Black people make up only 5% of the population of Tucson, a fact which some overly concerned with the identities of rioters and protestors fail to concern themselves with. The megaphone was passed among Black people in the crowd – giving them a chance to lead chants, yell instructions to white people, or speak to their frustrations with living Black in America.

Eventually we reached the intersection of Congress and Granada, in front of the Federal Courthouse. Almost every march in Tucson that wants to push boundaries ends up at this intersection, and the cops were fully prepared to shut down the streets and minimize any disruption to traffic. Until then we had seen only a handful of police blocking intersections and following behind the march, keeping their distance. In the evening haze, we heard demands for white people to put their “bodies on the line,” and “white people to the front,” however, the crowd formed a circle, “blocking” an empty intersection with no traffic in sight and no front to move to. Disagreements and frustrations mounted in the crowd as some white allies began to yell instructions at other white people in accordance with what some of the Black folks on the megaphone were saying, but then a different Black person would have completely different ideas as to what white people in the group should do, or whether anyone’s activity should primarily emanate from their social position at all. This confusion and tension slowed the motion and the morale of the crowd, revealing the limits of discourses which often exclusively operate on a level of representation and abstraction. Some people who appeared more prepared for a confrontation started to leave, clearly frustrated at the lack of clarity about what should be done. A couple American flags got burned in the intersection to lackluster applause and the crowd turned back toward the center of downtown.

As the sun went down, we noticed a few louder crews of young people shouting obscenities and challenging the white people in the crowd to do something more than just march. The first confrontation with the police came when a young Black man sat on the hood of a cop car and refused to leave. The crowd surged forward, clearly afraid the cops would arrest the man, but the situation diffused when the cops fled after removing him from the car. The cops were clearly rattled after this and the crowd grew more confident. We started to feel something like our own power. Shortly after, we heard something like “White Lives Matter!” shouted from the Ronstadt Transit Center, to which some young Black folks in the crowd responded by charging the person who shouted, fists flying. The crowd was torn between breaking up the scuffle and wanting to join in. When the two sides separated, someone threw a slice of cake in the racist’s face at which some laughed and moved on.

More active and visible coordination emerged among the crowd. Folks at the front attempted to decide which way to go. “Under the overpass would be easy to kettle, don’t go that way,” and, “There will be more people to see us if we go this way,” could be heard among the discussion. The questions of what white people should and shouldn’t do weighed heavy, which was intimately tied with what was and wasn’t risky for Black people to do. There was clear and palpable disagreement amongst the Black and Brown voices in the crowd as to what role white people should play – some would demand that the white people take a passive role, others would express confusion and dismissal of why any of it mattered in the first place. Much of this seemed devoid of any specific assessment of the situation we were currently in and remained attached to hypotheticals or general assertions based on different conceptions of privilege discourse. All this shifted when a Black woman said on the megaphone, “White people, we know some of y’all have skills to know what to do! Share them with us!” While this more tactical and specific question wasn’t the most repeated, it seemed to significantly shift the group mentality. Now, those elements within the nebulous mass that had a similar impulse could start to find each other, and a rhythm began to cut through the noise. The resonance of one act provoked a, “Yes and…” from another, and the riot that no one thought could happen took form.

Sent to us this morning. #kenosha #tucson #solidarity pic.twitter.com/tWlT38TAMl

— Autonomy Tucson (@autonomytucson) August 27, 2020

It wasn’t long before a couple rocks went through a window. When the first pane of glass fell it was surprising to hear how much of the crowd cheered. One of the young Black militants shouted, “Let these white people do that shit,” and while most non-white people didn’t seem to hold back, now neither did most of the white people. A large section of the crowd took this moment to go absolutely bonkers. Construction site materials and fencing were dragged into the street to obstruct the police vehicles following behind, countless rocks went through countless windows. Spray paint was handed out and slogans were painted everywhere, on everything. “We are together, kinda, we’re working on it,” “No more waiting 4 now,” and “We won’t stop until we’ve burned this shit down,” was scrawled amidst the flurry of “Fuck 12” and “ACAB” tags. At one point the crowd paused in a side street to decide what direction to go and everything was covered in slogans within 3 minutes. The group couldn’t have been more than 125 people at the absolute peak.

People who had seemingly never even disrupted traffic or moved in this way with a group were attempting to do so, together. There was certainly a learning curve and it was a little comical watching people in the front pull an entire construction fence into the street, effectively cutting the crowd in half. Others would then try to show more effective implementation of the tactic. Being good spirited in these moments was helpful to maintaining momentum and a feeling of cohesiveness. But it’s not rocket science and people catch on rapidly.

The crowd continued through downtown and then north to the 4th Avenue strip, the primary bar and trendy shopping district between downtown and the University of Arizona. “ACAB-19” and “We are going to take back our homes” were tagged on walls along the route. Interestingly enough, the crowd made no attempts to smash or loot any of the businesses there, with the exception of the Sun Tran street car stations. The Sun Tran is a pitiful excuse for public transportation improvement, obviously designed to shuttle and shelter students between the university, the hospital where med students train, the 4th Ave shopping district, downtown, and nowhere else. The pay stations were quickly smashed and George Floyd’s name painted along the way to nowhere.

The first dumpster fire was lit in the intersection of Broadway and Herbert Ave, to much excitement. More American flags burned in the fire and “Black Lives Matter, Fuck the Cops” was spray painted on the side of the dumpster. This first set of dumpster fires set off an obsession amongst the crowd, as every dumpster found in its path for the rest of the night became a flaming barricade in the closest intersection. The Arizona chain coffee shop, Cartel, got smashed up, while Thunder Canyon Brewery next door was spared. The people doing the smashing were heard multiple times discussing which targets were appropriate, and Thunder Canyon has hosted fundraisers and events for community-based groups, perhaps winning them a reputation further than they realize. This may not have spared other businesses with good intentions, but reputation certainly can be a factor.

The first few arrests of the night came when the crowd re-entered Armory Park to regroup. Numbers had thinned a bit and the cops seemed to take this opportunity to pull cars over and arrest people for helping hold the street in the back of the group. The group moved to the downtown police headquarters which had become an instinctive gathering point in almost every city after the burning of the Third Precinct. There couldn’t have been more than seventy-five people, but as the images of burning dumpsters, graffiti, and smashed windows spread rapidly across social media, new people gravitated towards the downtown precinct looking for the action.

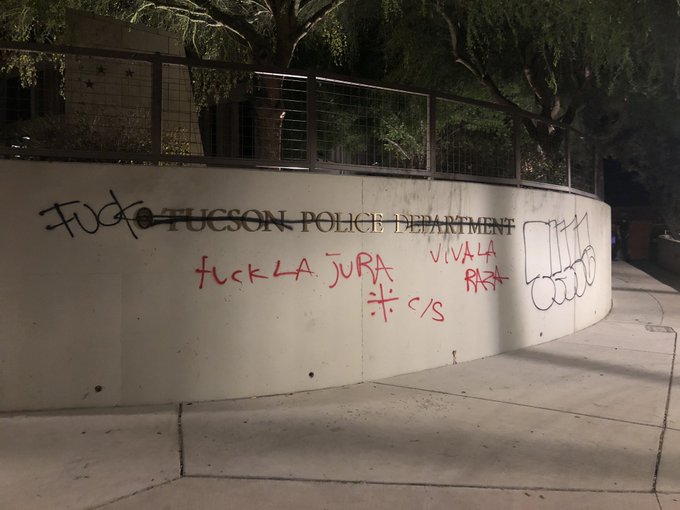

Right, all those white agitators were writing “viva la raza” on everything. Because that’s a thing that happens. No, we won’t share photos of non-white people fucking shit up because that’s how you get people arrested. Fuck off with your conspiracies. This is an uprising. pic.twitter.com/YAzSdRcJcY

— Autonomy Tucson (@autonomytucson) May 31, 2020

This was the first time that the police formed a line in riot gear, but not before the facade of the station was covered in “Viva la Raza,” “Fuck 12,” and “ACAB” tags. As new faces gathered in front of the riot line, holding their hands up and yelling at the officers, livelier activities accumulated in the back, closer to the dimly lit streets of Barrio Viejo. Young people drove slowly through the intersection, blasting NWA and Nipsey Hussle, hanging out the windows and shouting. The crowd swelled to around 300-400 people at the peak of the standoff at the precinct. Occasionally, a water bottle or rock was lobbed from this area at the riot line, and people in the front shouted for people to stop. This was the first time any significant shouts of “No violence!” could be heard, with seemingly no concept of the irony that their presence was precisely because people burned dumpsters and smashed windows. Policing doesn’t just manifest in riot shields, batons, and bullets, but in the heads of every citizen.

This was also around the time the first fight broke out within the crowd of demonstrators. Confrontations with journalists flared further splits over tactics within the crowd and some of the rowdier elements were expelled or left for fear of being targeted. Ironically enough, while the insistence on non-confrontation with the cops was often justified through the claim of “protecting” the most vulnerable, many of these crews were Black and brown. The party continued in the back for quite a while despite this, but a line had certainly been drawn by the activists that few felt empowered to cross. For the rest of the night, incursions by the police were met with bottles and rocks from the back, and the throwers were shouted down by the activists ever-worried about violence. A one-sided concern to be sure. Eventually numbers dwindled and the night ended in a sputter.

It is worth honorably mentioning that we caught wind of a banner drop and multiple large ACAB tags which appeared far outside downtown during the night. These acts took place occasionally throughout the first week, even during the curfew. This showed an encouraging spark of creativity and an attempt to engage the terrain outside of the militarized zone that engulfed downtown.

The Battle of 7th Street

May 30th, 2020

After the ruckus the night before, you couldn’t go anywhere without hearing about it. A speak-out on the university campus was canceled, city officials stood with the police chief to condemn the murder of George Floyd and also the violence of the demonstrators. The local news was full of reports surveying the damage and the controversy. This familiar story played out across the country. Clips of Black “leadership” claiming the rioters weren’t Black were juxtaposed with clips of Black rebels rioting in the background.

As night grew closer, people gathered at the University of Arizona despite the official event getting canceled. There was too much momentum for any self-appointed organizer to cancel anything. Now a crowd of around 700-800 people marched their way between the university and downtown. This crowd went relatively unencumbered by police for a couple hours, despite graffiti crews leaving a trail of tags, slogans, and the rich smell of spray paint in their wake. The march circled back to the campus to have a speak out under the buzz of helicopters. Riot police assembled downtown and it was obvious the scenario was going to play out much differently from the night before. After a long speak out from predominantly Black students ended, the crowd began to move again. About 300 people made their way back toward downtown, but were immediately met with a riot line at the underpass entering downtown. This became the primary dynamic of the night.

Downtown Tucson is cut off from the entirety of the north side of the city by train tracks that run east to west across the northern boundary of downtown. All the main roads and sidewalks flow underground through multiple underpasses to enter downtown. The group’s obsession with going to the downtown police station became the primary limitation on the activity of the night. Marches split up and converged multiple times through the evening, attempting to find a way around the police lines easily blocking the underpasses. Sometimes small groups would light fires in the street or attack businesses along the way, but rarely did this serve much material purpose beside catharsis. No new opportunities were opened up by these acts because the vast majority of people on the streets still saw it as the goal to reach downtown. The crowds didn’t feel brave enough to attempt to break the police lines, likely in part because the police clearly had the tactical advantage. Their lines were formed up the hill with the crowd trapped in the underpass. This changed at the battle of 7th Street.

Tucson protest/riot, May 30th, 2020. It started off as a peaceful march. Police then blocked protestors from entering downtown and shot pepper balls towards crowd. Citizens set trash cans on fire and protested for hours @whatsuptucson @DanMarriesKOLD – TMZ Tucson pic.twitter.com/VOonUCM9Yz

— TMZ Tucson (@TmzTucson) May 31, 2020

The one place that traffic is not forced underground to get into downtown is where 7th Street and 7th Ave converge. This low traffic intersection feeds across the tracks at ground level into downtown, intersecting shortly afterwards at Toole Avenue. Once again, the demonstrators converged on this point, headed off by only a small and weak riot line of police. This was a decisive moment of the night because as the crowd attempted to move across the tracks, an approaching train was heard and the crowd hesitated. Suddenly, mobile units of uniformed Arizona State Patrol officers pulled up to the crowd on 7th Ave, jumping out of unmarked SUVs and pelting the crowd with pepper balls. This pushed the crowd back up 7th Street, going east. This was our first encounter with these units. They would be the primary force to deploy chemical weapons for the rest of the summer. So begins the battle of 7th Street.

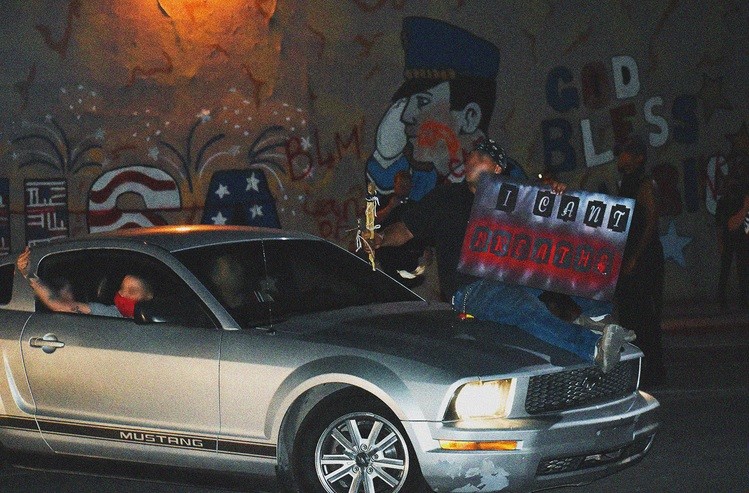

The primary clashes of the night took place along 7th Street between 7th Ave and 5th Ave. Occasionally, small groups broke off and attempted to find another way around, but there was no feasible path for any more than a handful of people to cross the tracks without meeting riot cops. A similar scene as the night before played out at the intersection of 6th Ave and 7th Street. At the front, activists held their hands up and pled with police, while the people looking for something more interesting to do hung in the back, partying out of cars and covering the patriotic mural on the side of Miller’s Military Surplus in graffiti. Occasionally a rock or bottle was thrown from the back, only to be shouted at by people in the front. There seemed to be an obvious split this time between students (often in the front, Black and white, stickers on their water bottles, camelback packs on their backs) and the more heterogenous grouping of people in the back. This party element was more multiracial and read as more “subcultural.” Cholos would slow roll in their cars blasting music while hardcore kids, punks, graffiti writers, and street youth roamed about looking for materials to start fires and windows to break. Often those in the front wore nothing but cloth covid masks and tank tops, while those in the back donned t-shirt masks, athletic wear, or a combo of bandanas, hoods, and hats.

This long standoff, with occasional clashes and incursions from the cops, played out for what felt like a few hours. Our crew walked off to take a break and see what else might be happening in the area. As we wandered back, we heard a couple gun shots and observed a portion of the crowd fleeing east down 7th Street. When we got closer, we could see an SUV swerve through a cloud of dust, the crowd splitting to let it through. The driver was waving a handgun around and it was unclear at first whether he was firing into the crowd or at the police. This was a jarring moment as he let off more shots in the direction of the riot line and sped off. As plenty of friends have observed, the presence of firearms can play decisive roles in these situations. The tactics we choose to employ in a moment can be what tips the scales in one direction or the other, they can make a crowd feel powerful or completely disempowered. This moment seemed to do both.

People had been in the streets, in over 100-degree heat, since the afternoon. Throughout the summer this factor cannot be overstated. It was exhausting. This, combined with being repeatedly unable to reach downtown while also refusing to direct energy anywhere else resulted in a collective exhaustion that, for a lot of people, seemed to reach its end point after the erratic gunman in a car wildly shot at the cops. A sizable portion of the already-demoralized crowd was now afraid of getting shot. A smaller portion of the crowd stuck around, adrenaline pumping, sweaty, and wild eyed. The police, likely also full of adrenaline at this point, made a push for the crowd to move further east down 7th Street. This was the first whiff of tear gas of the long summer. In response, the determined group of rebels quickly lit a dumpster fire next to Miller’s and used nearby construction equipment to build a barricade further down the block. Traffic signs became shields against pepper balls, and rocks were pelted at the cops at regular intervals. The activists had all gone home after the gun shots, but so had many others. There couldn’t have been more than fifty people left, facing off with over 100 riot police, a helicopter, and snipers on downtown roof tops pointing at people from hundreds of yards away. This clash went on for almost an hour, until finally the mobile units in SUVs flanked the small crowd from behind, released multiple canisters of tear gas at once, and attempted to snatch multiple people, scattering the crowd and ending the night. Remarkably, some people were de-arrested and at least one SUV got its window smashed in the melee.

Counter-Insurgency 101

June 1st, 2020

In a fairly typical act out of the counter-insurgency handbook, organizations associated with the City of Tucson government quickly announced a vigil, to be held at the Dunbar Springs Pavilion. It coincided with the first night of the city-wide curfew that started at 8pm. Dunbar Springs, just north of downtown, is one of two historically Black neighborhoods in the city. The neighborhood has been thoroughly gentrified over the last twenty years and few remnants of the old neighborhood remain. This was the first time we saw a crowd of this size, close to a thousand. Many local Black activists vocally opposed the vigil, as it was clear to anyone paying more than a few seconds of attention that it was an effort to co-opt and pacify the rage and anger sweeping across the country. The attendees overflowed the pavilion and into the street. There were certainly people of all ages present, but this was by far the whitest and the most docile. Various spokespeople gave speeches, pleading for peace and invoking Martin Luther King, Jr. The vigil ended by reading the names of Black people killed by the police. Many of our friends moved to the front, as we had been told a group of queer Black people would attempt to take the stage. As some young folks stood on the stage and shouted, it was demoralizing to see how few in the thinning crowd seemed to even notice that something was happening. A few hundred people stuck around, largely young, and shouted, “Let them speak!” Speeches were attempted but largely went unheard, as the men who seemed in charge of the official event refused to allow the younger group to use the mic.

Sent to us anonymously: #Tucson #georgefloyd

Candlelight Vigil for George Floyd at The Dunbar Pavilion

we have to rid ourselves of contradictions. why would any event be co-hosted with the enemy?

no space should be given to the pigs ever, but especially not in this moment.

— Autonomy Tucson (@autonomytucson) June 5, 2020

Not long after, closer to the university, a small group attempted to march and defy the curfew, but they were quickly broken up and twelve people were arrested. We didn’t know it at the time, but this would signal the end of the revolt itself in Tucson. The curfew and the activists had demoralized the uprising enough to crush it. However, there was an explosion of energy and activity in the city that would last most of the summer, the high points of which we will attempt to highlight below.

The Activist Turn

June 6th, 2020

For the next couple months there would be a march, protest, or other political/activist event once a week or more, which is unusual for Tucson in recent years. It would be impossible and honestly boring to mention every event that took place over the summer. While many of the events resulted in new people finding each other, many of them were small and exhausting. The local chapter of Black Lives Matter hosted a Celebration of Black Lives on the University of Arizona campus after initially announcing they wouldn’t be planning any public events. The hours-long event brought together poets, activists, students, and musicians to perform and speak to a crowd of thousands. The temperature was in the upper nineties–relatively cool compared to the rest of the summer.

As the event wrapped up and some of the thousands began to disperse, chanting swept through the crowd as a march stepped off campus and took the familiar route towards downtown. This was the biggest march all summer. It snaked towards downtown and through the West University neighborhood, numbering around 1,200 people. The group paused near the intersection of Stone Ave and 6th Street, debating whether to go downtown or try something new. This time, some contingents in the crowd had come much more prepared. After some debate, the crowd began marching toward the westside down 6th Street, and a mobile sound system made its way to the front of the march. People made requests and got excited, some dancing and many laughing. The energy built in the crowd as we passed under the I-10 overpass, taking a left south towards the on ramp. It was clear that the intent was to take the highway, and the crowd started moving faster with excitement. There were very few cops in sight. The t-shirt masks came out and “Black Lives Matter,” “Fuck 12,” and “ACAB,” appeared in spray paint on walls. We danced around prickly pear cactuses and landscaped ocotillos, and cheered as the first people climbed onto the highway with only a few State Patrol cars to meet them.

Strangely, when those on the highway looked back, very few of the crowd had followed. Appeals were made to join the group on the highway. Some demanded white people put their bodies on the line, some insisted there were no cops, some said, “safety in numbers.” No appeal seemed to work. This collective hesitation once again allowed the State Patrol–this time the highway division–to amass more numbers on the highway. These seemed to be the same units encountered back on May 30th by the train tracks. Some of the vehicles were unmarked and they quickly deployed pepper balls at a few people on the highway. At least one protestor responded by attempting to break the window of a patrol car. Then the State Patrol let off a smoke bomb, which seemed to startle the already-timid crowd below. Many demonstrators scattered into the wash of the Santa Cruz River. The police also seemed erratic and unprepared: we witnessed an officer jump out of his vehicle with no helmet, wildly attempting to fire bean bag rounds at those facing off with him, not realizing his safety was on. The protestors took this opportunity to heckle him mercilessly, of course.