June 2019

From The New Inquiry

Liz Kinnamon

The criminalization of humanitarian aid at the border enacts a fantasy of desolate individuation. Scott Warren’s felony trial reiterates the necessity to keep reaching out.

Painting by Cesya Palmer “Empire is the style of revolutionary terrorism, for which the state is an end in itself. —Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

ACROSS from the Tucson federal courthouse, where Scott Warren’s felony trial is taking place, a group of prisoners in orange rake the leaves of a towering mesquite tree. Their pant legs bear the stamp of Arizona Department of Corrections, “ADC,” and the tangerine monochrome of their uniform blends with the Caesalpinia pulcherrima shrub they tend — a shocking flower that grades from orange to red.

This flower—otherwise known as pride of Barbados, peacock flower, or Mexican bird of paradise—is native to the West Indies and was made famous by the German-born artist and naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian, who traveled to the Dutch colony of Surinam in 1699 and published paintings of it in her book Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In a vague account of a conversation she had with enslaved West African women, Merian explains that Indigenous and West African slaves in Surinam used the seeds to induce abortion and commit suicide rather than reproduce or live for their white owners. Merian, a slave owner herself, used this information to caution other Europeans in Guinea and Angola about their slaves’ reproductive insurgency.

Although Merian’s book documented the peacock flower as an abortifacient, knowledge of the plant’s uses did not transfer to Europe. Only the flower itself did: It grew in gardens across Europe without its context. Not necessarily because information about it was repressed but because it was omitted by European male elites who were “hard set against abortifacients,” especially those of Indigenous or Black origin. In her book Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World, historian Londa Schiebinger notes that one word for the study of such elision or nontransfer of knowledge is agnotology, or “the study of culturally-induced ignorances.” In contrast to epistemology—the study of knowledge—agnotology centers what is not known and why.

When I phone the Arizona Department of Corrections, the operator tells me that the men working by the flower make 10 to 50 cents an hour. They might not know about the plant’s uses, and an agnotological explanation would be that they do not know precisely because Merian did. She warned European colonists about the plant, and the information stopped traveling. The incarcerated or otherwise coerced are the very people in whom colonial Europeans would have liked to cultivate ignorance of the plant’s powers.

The shrub, the men, and the tree branches sway in the hot desert wind, forming the foreground of this picture. In the background stretches a tile mural of the American Dream.

For responding to the encounter by providing care, he was charged with one count of conspiracy and two counts of harboring under 8 U.S.C. § 1324(a). This harboring statute in the U.S. Code, which criminalizes someone who “conceals, harbors, or shields from detection” a noncitizen, is open to interpretation because it doesn’t define the words “conceal,” “harbor,” or “shield from detection.”Scott Warren’s felony trial is taking place in the courthouse across from this scene. The No More Deaths / No Más Muertes (NMD) volunteer faces three felony charges for providing humanitarian aid in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands near Ajo, Arizona. He arrived one afternoon at “The Barn”—a house in Ajo, Arizona, used by multiple humanitarian aid organizations as a staging ground for water drops, medical aid, and search-and-rescue operations—to find two men there in need of food, water, and medical attention. Such an encounter is normal for borderlands residents who commonly come into contact with migrants crossing the desert in bad shape. The two men had been traveling on foot for days and had been away from their home countries of Honduras and El Salvador for months. Scott performed medical assessments, as required by No More Deaths’ medical protocol, and found that they had blisters on their feet, had respiratory issues, and were likely dehydrated. He provided rest, food, and water to the two men.

The case is titled United States v. Scott Daniel Warren, and the prosecutors introduce themselves in court as representatives of the United States government. It’s the second trial Scott, his friends and family, humanitarian aid groups like No More Deaths and Ajo Samaritans, and other supporters have endured in the past month. Earlier in May we were here for his misdemeanor case, which still awaits a verdict from Judge Raner C. Collins. Scott faces one misdemeanor for placing food, water, medical supplies, and blankets on designated wilderness in Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and another for driving on administrative roads in the refuge. These roads are necessary if one is to reach what mapmaker and retired geosciences professor Ed McCullough calls the “trail of deaths” in the Growler Valley.

Scott is a geography professor who has taught at both Tohono O’odham Community College and Arizona State University. His dissertation, “Across Papagueria: Copper, Conservation, and Boundary Security in the Arizona-Mexico Borderlands” (2015), focuses on the history of migration, the mining and border-patrol industries, and the changing geography of what is now known as southern Arizona and northern Mexico. Early in his dissertation he explains that in southwestern mines, the majority of miners and general laborers were either Mexican or Indigenous—not white. While Mexican and Indigenous workers were doing the lowest-paid manual work, white men were listed in the 1920 census as “skilled workers, managers, and foremen.” Scott’s work exposes the narrative told in the mural pictured above as either false or quite truthful, depending on how you look at it. It depicts the historical reality of southwest Arizona only inasmuch as empire situates itself at the center of the world and claims the fruit of the labor it simultaneously exploits, a move rendered through the figure of the blue-eyed miner. Or, the contextual view of the mural is closer to the truth of labor in Arizona, with prisoners of color laboring beneath it and cacti recruited for state decor.

If there is a single lesson of the judicial branch, it’s that, like the mural, the same narrative can be entirely true or entirely false depending on how you look at it. One might play these perceptual tricks silently with oneself while sitting in the audience of the court.

***

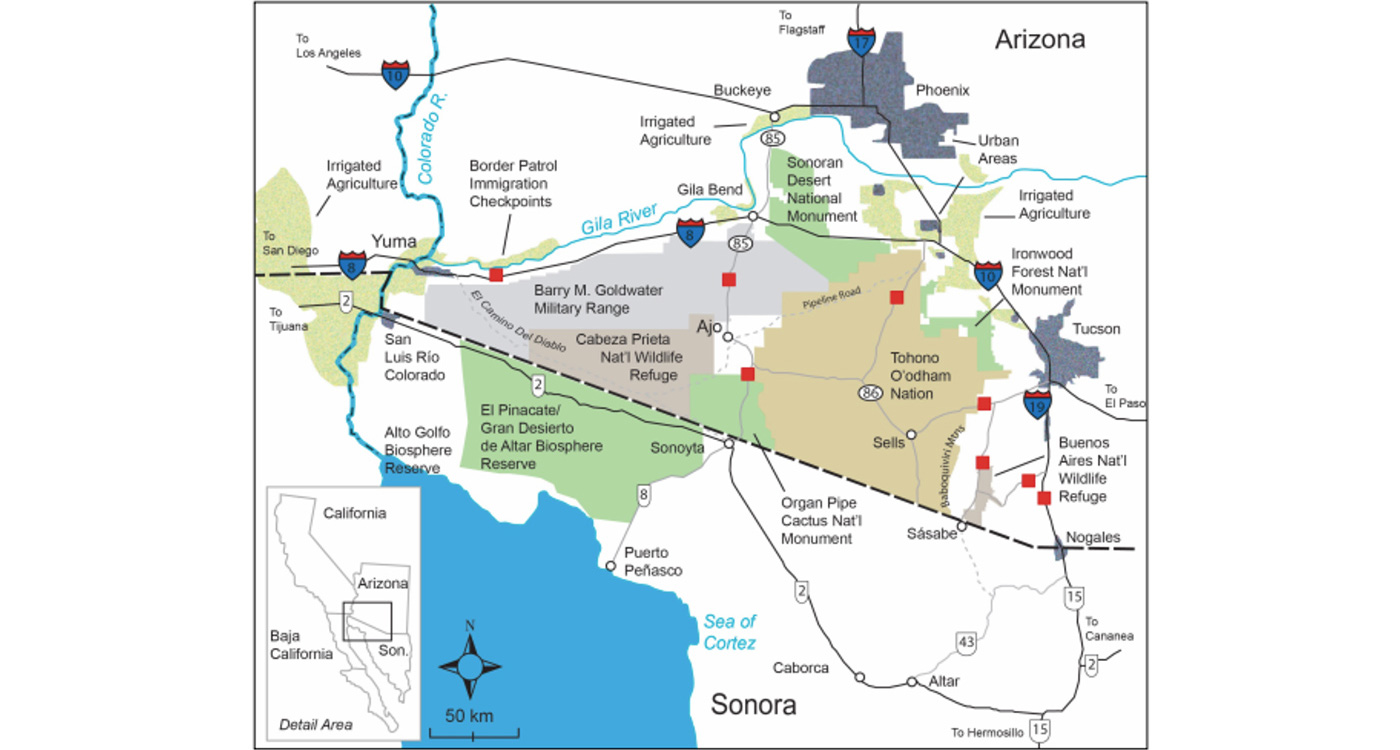

The town of Ajo, where Scott lives, borders Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge,

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, the Tohono O’odham Nation, and the Barry M. Goldwater military range.

The U.S.-Mexico border is about 30 miles south. This map was created by Scott Warren and can be found in his dissertation, “Across Papagueria: Copper, Conservation, and Boundary Security in the Arizona-Mexico Borderlands” (2015).

The public outside the courthouse receives a narrative outline of the trial that is different from the phenomenological experience of being in the courtroom. Via the news, for example, those following along know that Scott was arrested on January 17, 2018, at “The Barn” in Ajo, a region of Arizona that is located in what No More Deaths calls “the west desert”.—“one of the most frequently traveled and deadly migrant corridors in the Sonoran Desert.” The public might know that on the morning of Scott’s arrest, NMD had released video documentation of Border Patrol destroying water gallons for migrants in the desert. In what No More Deaths views as retaliation, BP set up surveillance of The Barn that afternoon and saw Scott speaking with two men they assumed to be undocumented migrants, Jose Arnaldo Sacaria-Goday and Kristian Gerardo Perez-Villanueva. BP soon arrested all three. The U.S. government kept the two migrants as material witnesses for Scott’s case—promising them that in exchange for testifying they would not be criminally prosecuted—and then deported them in early 2018. The U.S. government then charged Scott with conspiracy and two counts of “concealing, harboring, or shielding from detection” the two men. The public might know that the U.S. government is trying to spin Scott’s provision of food, water, medical care, and rest as criminal intent to further the men’s presence in the United States. And finally, readers might also know that the felony trial took place from May 28 to June 11, 2019, and that it resulted in a hung jury, with eight for “not guilty” and four for “guilty.”

In receiving this outline, what the public might not see is that the simple architecture of a court case is necessarily arrived at, or achieved, from a complex, long, and hazy stretch of proceedings. Differently put, the totality of events in a trial is put through a sieve. One must distill and pan out repeatedly in order to extract what becomes the overarching story. This is because the experience of a trial is less like a plotline and more like a string of atmospheres one passes through. Those in the courtroom are riding two parallel tracks: the plot and the clusters of meaning that cohere and disperse along the plotline.

Arrest – Opening Arguments – Witness Testimonies – Closing Arguments – Jury Deliberation — Verdict

Hundreds of microclimates mushroom inside this chronology. We could also call them meaning-formations. They are minor perceptions, like body language or a smirk. Or they are rhetorical exchanges between the witnesses, judge, jury, prosecution, and defense that collaboratively make meaning. One example is the cluster of meaning that formed about “consent” in the trial, which I detail below. It is pertinent to tease out the lesser-discussed microclimates because paradoxically these minor moments reveal profound philosophical, ethical, and political dispositions of the state. Embedded in them is information about how the state views and treats life.

One accesses the importance of micro-moments by refusing to acclimate. This means that methodologically the goal is to never lose sight of the strangeness of the juridical sphere and its socially constructed nature. Regardless of how long one sits in court, how many trials one attends, or how much one knows about the law, the strategy is one of estrangement and its permanent maintenance.

This is another way of saying that if we see life as always becoming or being made, it can be made different.

***

During jury selection, Judge Collins went through about 50 potential jurors to arrive at the final 15. Many in the jury pool were corrections employees, wives and mothers of Border Patrol agents, or law-enforcement officers themselves. They were eliminated, along with jurors who had any knowledge of the humanitarian crisis in the borderlands—whether they’d volunteered for Humane Borders or simply heard of the organization. What remained was a pool of majority-white jurors (11 women, 4 men) that somehow qualified as “neutral.”

The jury was not only selected for ignorance but mandated to it by being restricted from context about the case. Per procedure, Judge Collins read from the Ninth Circuit manual of jury instructions and told them not to read any news articles, view social media, or conduct any research. They weren’t to discuss the case with friends, family, or other jury members. “You will get everything you need to decide this case inside the courtroom,” he said. “At the end you have to make decisions based on what you remember. Pay attention. Take notes.” He explained that people can’t consult outside sources, because then some jurors would have knowledge that others didn’t. But you can’t control for mnemonic accuracy, individuals’ past experiences, perceptual acuity, epistemic drive, or compassion. Some jurors walked in with a mind they gave up on years ago. Others were asleep. As commonplace as these jury instructions are, they comprise basic errors and assumptions about knowledge that in part determine the fate of human beings.

Judge Collins also informed the jury that regardless of whether they spoke Spanish, the only valid interpretation was that officially provided by the court. He was referring to the video depositions of Sacaria-Goday and Perez-Villanueva, which the prosecution taped on March 7, 2018, and played on screens throughout the courtroom in Scott’s felony trial. In the videos, the translator, a woman of about 50 years, sits close beside each of them when they take the stand. She is a buffer, an accomplice, and an enemy all in one. The U.S. attorneys begin the interrogations of both men with the infantilizing question, “Do you know what it means to tell the truth?” They didn’t ask any of the other witnesses in Scott’s trial this question. The interpreter has to translate this.

Whether the two men were ever inside The Barn is not in question—the problem is whether their being there constitutes criminal harboring or humanitarian aid. Or, whether humanitarian aid is indistinguishable from criminality.In the videos, the prosecution trots out a mind-numbing array of minutiae. They show endless pictures of The Barn’s interior, different views of the same room, and the building’s architectural layout for no reason other than to build a Law & Order air of suspicion among jurors.

The aesthetic choices of the state are particularly astonishing in their amateur character. Any photograph of any quality could be viable evidence: rinky-dink or after the fact, reliable or not. Photographic and textual evidence is placed onto the projector’s glass plate and displayed on the courtroom screens, projecting along with it the prosecutor’s shaky hand or the enlarged hairs on an attorney’s arm. Through an estranged, queer, and repurposed view of evidence, one looks out to find that “proper” evidence is distinguished only by the material force of large-scale violence that backs it, not its quality.

Jose and Kristian’s video testimonies are professionally edited: Video of the witnesses appears above rolling transcription so that the jury could read while watching. Sometimes, even though photographic evidence was integrated into the video by the court’s editor, the U.S. attorney comes around in front of the camera and holds up the physical photographs, his face suddenly breaking the fourth wall. These moments have the found-footage feel of The Blair Witch Project.

It is through these videos that the court is first introduced to the evidence that the U.S. attorneys really believes seals their case: selfies the men took on their journey. Retrieved from Kristian’s phone because Jose tossed his cell, food, and water when chased by Border Patrol, the photos that have the most impact are the two men smiling with volunteers at The Barn, a photo of Jose and Kristian happily cooking dinner, and a shirtless selfie of Kristian in the bathroom.

The photos are provocative, in part, because the men are smiling. Referring to one photo, the U.S. attorney says, “You don’t take that photo if you’re not feelin’ good about how you feel.” From a strictly literary perspective the prosecution’s argument is awful, but it also suspends basic facts like representation ≠ reality; selfies do not provide straightforward, nonideological, unaltered, or “natural” information about life; and the relationship between social-media use and affect is complicated. As No More Deaths tweets, “Expressing relief or joy through suffering is not a crime.”

But a blaring subtext of the government’s evidence is sex. Kristian’s gleaming torso and the logo-strewn strip of his briefs send silent lightning bolts through the court. His structured hand holds the camera to the mirror. The U.S. argues that Kristian was not in need of food, water, or medical care because of this selfie. The U.S. attorney nearly scoffs when she shows the shirtless photo to the jury. “Do you see any cuts or scratches on him? No, he’s doing just fine.” I recognize what is happening as the noxious blend of shame, desire, and abjection that constitutes racism. The potential for desire and repulsion evoked by an Other — in this instance Kristian’s racialized embodiment — mirrors what happens at the border between one nation and another. Sexuality is a central element of border logic: Expel what’s compelling enough to scare you, then draw a clear line between it and yourself.

The prosecutor shows Jose one of these photographs and asks, “Do you know who that is?”

“Us.”

“By ‘us’ who do you mean?”

“Us. Us two. That’s us two.” The sleeves of Jose’s shirt are pulled over his hands. He is simultaneously flippant and gentle, barricaded and flirtatious. He dodges clarity.

“What were you doing?” the prosecutor aggressively demands.

“Posing,” Jose smirks. It’s a stupid question. “Posing for the picture.”

The interpreter can’t help smiling and laughing as she translates Jose.

Jose mumbles something to the translator as a follow-up.

“In the kitchen area,” the translator says, “where we were kissing—cooking. I’m sorry, cooking. In the kitchen cooking.”

The translator laughs anxiously. Jose smiles with his sleeved hands. The two of them laugh together on the witness stand.

[kitchen – cocina – kissing]

After the prosecutor has moved on to another line of inquiry, the translator interrupts to clarify that the bit about kissing was her slip of tongue.

Two older jurors whose body language has been leaning toward each other throughout the trial giggle and look at each other when she makes the correction.

The contagion of humor and desire. The borderlessness of it.

When the prosecutor asks Jose how he got from one gas station to another after crossing, Jose says with a smirk, “We asked a gringo for a ride.” He laughs. She laughs. She translates this too.

***

The defense calls Dr. Norma Price, and she is untouchable. Razor sharp, with a southern drawl, Norma went to school in Tennessee, practiced oncology in Atlanta, and has been declared a “hero” by Physicians for Human Rights. She is the medical consultant for No More Deaths. Jose and Kristian had been walking for days and sleeping on the ground in January, putting them at risk for hypothermia. They also had blisters that put them at risk for infection. Scott performed a medical assessment of each when he found them at The Barn that day in January. Because the prosecution had been spinning Scott’s willingness to give the migrants food, water, and rest as “concealing” them from detection, his defense team is trying to establish the basic fact that dehydration, open wounds, and low body heat are life-threatening. They are also trying to establish the fact that rest is needed for human survival. Things have gotten that base, but they get even lower.

Defense lawyer Greg Kuykendall asks the doctor, “Can you tell from a surveillance video or a selfie whether someone is dehydrated?”

Norma responds, “Course not.”

The containment and inexpressibility of pain. The bordered-ness of it.

Theorist Elaine Scarry likens the occurrence of pain in another’s body to a subterranean event unfolding in an invisible geography, an event that fails to register as real because it does not emerge onto the surface of the earth. Pain is not always visible, and even when it is, no consequences inhere in that visibility. It is still inaccessible. Just because you see it doesn’t mean you feel it. And even if you establish that someone is in pain, if they’re a migrant and you’re the U.S. government, their pain is secondary to the fact that they’re “illegal.”

When U.S. attorney Nathaniel Walters cross-examines Norma, he asks, “In a perfect world, face-to-face is best for diagnosing. Right?”

She pauses, stunned, then incredulously threatens: “Do you want me to talk about a perfect world?”

Sensing a dead end, Walters pivots to the issue of “informed consent.” Earlier in the week the defense displayed sections of No More Deaths’ protocols in order to establish that the organization’s provision of humanitarian aid was within the bounds of the best legal and medical practices. But in the government’s cross-examination of Dr. Price, they zero in on one line that advises volunteers to explain the potential consequences of all medical options, including the risks associated with calling 911.

From this point forward, the U.S. attorneys try to prove that No More Deaths—and Scott by extension—seek to conceal migrants from Border Patrol when they ask consent before calling 911. It soon becomes clear that every witness who has volunteered with No More Deaths believes consent is a basic requirement of providing health care, while the witnesses for the prosecutors do not. “I always make decisions based on the consent of my patients,” says defense witness nurse Susannah Brown. “I’ve sworn an oath. The Nightingale Pledge asks that I do the best I can do for my patients at their direction. Any human being deserves that dignity.” Law professor Andy Silverman, also a witness for Warren, explains informed consent this way: “It’s not the place of a lawyer or nonlawyer to make a decision for anyone else.”

Statements like these, which assert one human being cannot act upon another in whatever way they please, feel monumental at this moment in court. A friend half jokes at dinner that night, “It’s exhausting sitting around all day listening to men talk about consent.”

When U.S. attorneys call BP agent Gerardo Carrasco to the stand, a paramedic with Border Patrol Search, Trauma, and Rescue (BORSTAR), he says, “I do not ask for consent before calling 911.”

“Never?” the U.S. attorney asks gleefully.

“Not ever.”

“Nothing that would require you to get consensus before calling 911? Nothing in your ethics?”

“No.”

When the defense gets their chance with Carrasco, they ask if he knows what Prevention Through Deterrence is—the official Border Patrol policy detailed in the 1994 Strategic Plan that closes off urban entry points and pushes migrants to walk through the deadliest parts of the desert in hopes that death and hardship will deter migrants from crossing. He says he hasn’t heard of it even though he’s been with BP for 20 years. He also claims never to have seen maps of human remains made with data from the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner and not to know that over 3,000 people have died in the desert since the 1994 policy.

At one point, the U.S. attorney implies that not calling 911 because a migrant wishes not to be turned over to Border Patrol could result in their death, and that this would be negligent medical practice. Dr. Price retorts: “Death is not unethical.”

***

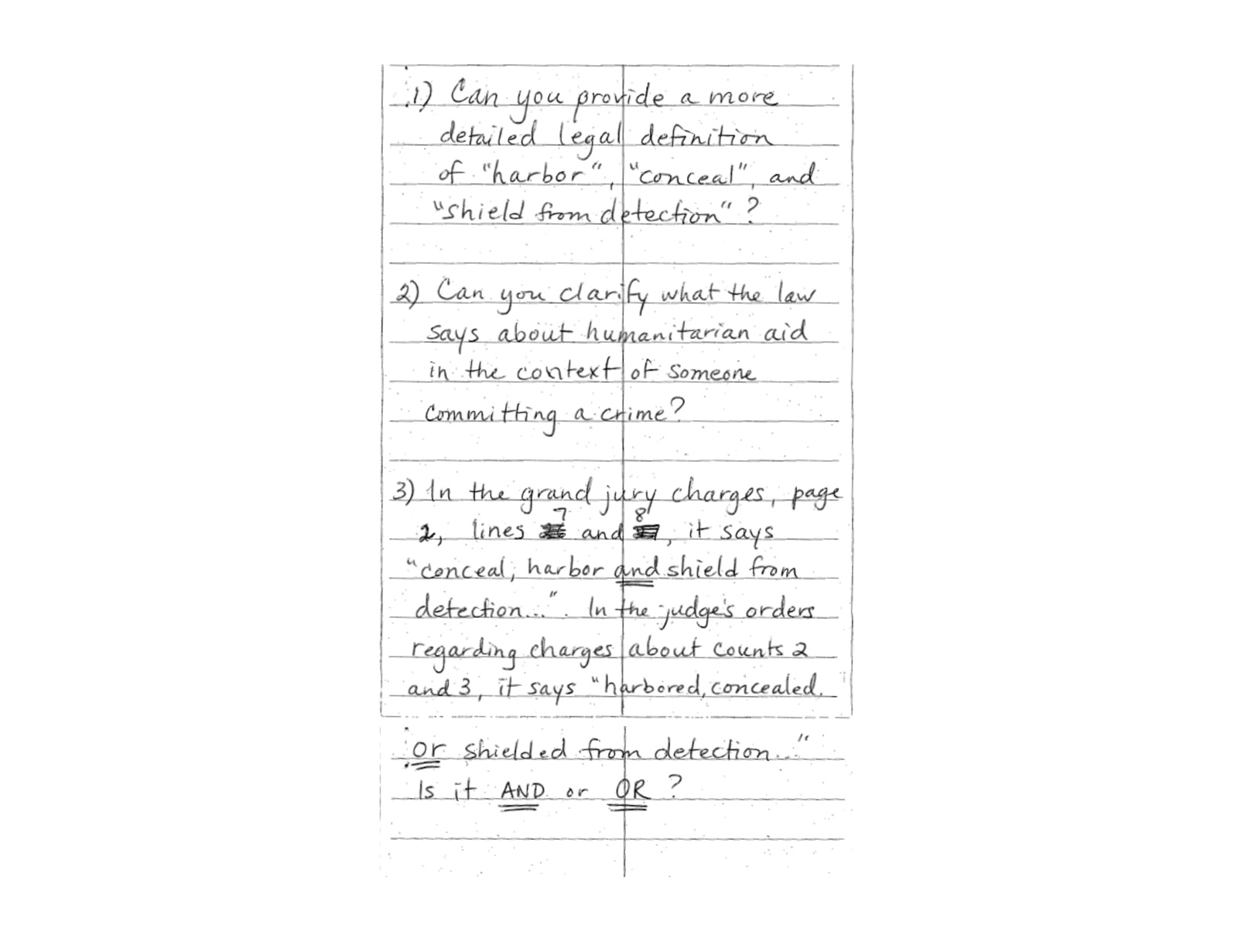

While the jury was deliberating, a juror sent this series of question to the judge. It speaks both to the intellectual rigor of the juror and to the contingent, vague rhetoric of the law. The judge responded, “In answer to Question #1, Harbor means to provide shelter to. There is no further definition of conceal or shield from detection. In answer to Question #2, all three counts require the proving of intent to violate the law. In answer to Question #3, It is harbor with intent to violate the law or shield from detection with intent to violate the law or conceal with intent to violate the law.” Document retrieved from Court Listener.

***

An older volunteer with No More Deaths is sitting beside me when Scott takes the stand. He pulls something from his pocket that I assume is ChapStick. Moments later, I see he is rubbing a small stone.

***

When nurse Susannah Brown testifies about her medical assessment of Jose and Kristian at The Barn, she explains that Jose had some kind of chest injury. He had fallen during his journey and might have had a fractured rib or an upper-respiratory virus. She knew because his lungs weren’t expanding fully, and she could hear small crackles in them when she used a stethoscope. “Crackles?” an attorney asks. “Yes, it sounds like when hair rubs against itself.” A friend sitting beside me leans down and rubs their hair together so we can both hear it. “Slow, deep breaths could be a remedy for the crackling sound because it opens up the lungs,” Brown says. I watch and feel the bodies around me expand their lungs.

The contagion of breathing. The borderlessness of air.

***

In the Warren trials, U.S. prosecutors made a slew of philosophical arguments that might be known characteristics of the nation-state but are seldom spelled out with such clarity. I’ll gesture to three of them here.

The first is that the nation-state wishes to reduce and simplify. When pressed to confirm that he is a “high-ranking leader in No More Deaths,” Scott paused and smiled—not because he was plotting a lie but because the government doesn’t understand horizontal power structures. “He paused,” was the U.S. government’s argument as to why Scott’s testimony was not credible.

Second, the nation-state relies on a myth of “common sense.” When asked about the spirituality that calls him to practice humanitarian aid in the desert, Scott gave an immense description of the sacredness that inheres in places where people suffer. On the spot, he defined the word “place” like a practiced philosopher. In response to this carefulness and complexity, the U.S. government wielded an anti-intellectual appeal to argue that Scott’s way of speaking was “obscure” and thus untrustworthy. In both of these instances, the state advocated a devaluation of complexity, contemplation, and carefulness.

The third is most succinctly demonstrated by the debate that took place in the courtroom around the difference between “giving directions” and “orientation.” The prosecution argued Scott gave directions so that the migrants could avoid BP checkpoints, and their evidence was that, through a surveillance scope, BP agents had seen Scott “waving his hands around” toward the mountains while standing with the two men. Asked to define, as a geographer, the difference between orientation and directions Scott said: “Orientation is partly an art and partly a science, of being able to tell where you are in relation to the landscape.” His attorney argued that “orientation is just as much of a human right as food, water, and shelter. Humanitarian aid organizations around the world recognize the reality that migrants are going to migrate. No More Deaths’ mission is to reduce harm.”

From barring video evidence of recovered human remains in court, to denying individuals the right to know where they are, to arguing that we all cut off natural flows of generosity that would compel us to give water to someone directly in front of us, every argument presented by the U.S. government in United States v. Scott Daniel Warren sought to deny context. This is the final philosophical position laid bare in the Warren trials: Decontextualization is an ideological state project. Prosecutor Anna Wright said as much in her closing argument, and in so doing laid out one of the most profound ethical positions of the U.S. government: “Context [is] another fancy word for confusion.”

To the contrary, context is an ethical imperative. It is an imperative for life. Retain it, insist on it. Just as European colonizers clipped plants from their native ecologies, planted the seeds in faraway gardens, and robbed millions of their social and historical uses, U.S. empire wishes to deracinate us all from our web of relations. Put differently, power is actively producing a not-knowing wherever isolation is at play. Division is not always a bad thing—people produce beauty, contemplative demeanors, and commitment from it all the time. But it is to say that decontextualization is a tool of power that can be put to various ends. If agnotology is the study of what is not known and why, we must all be agnotologists.

***

No More Deaths recognizes that United States v. Scott Daniel Warren and other prosecutions of humanitarian aid workers around the world are show trials for increasingly fascist administrations. By criminalizing the provision of care to anyone in need regardless of status, these governments mean to expand the definition of harboring. The effect of such expansion is to contract the scope of life on this planet.

In the same way that capital wants to transform contact into exchange, the state wishes to turn every point of contact into a checkpoint. “You could’ve given them food, supplies, and said ‘good luck,’ but you didn’t do that,” the U.S. attorney said to Scott Warren.

“I didn’t—I guess you could say—kick them out, no,” Scott replied.

One lesson of Scott’s case is that the state is trying to crowdsource the checkpoint. It is trying to make you into the border. It is our job to understand the vicissitudes of boundary lines—to know what they’re for and how they’re used. To be wary. For all the cautioning against paranoia, paranoia is protective armor against the dulling encounter of face value.

To refuse to be the border is to resist locating what scares or excites you as entirely outside of yourself.

Our job is to keep reaching out. That is already a heroic feat in a world trying to erase contact altogether.