November 2021

Anonymous

PDF of Zine

1. Explosions

“If the popularity of... the various Lethal Weapons or Die Hards reveals anything, it is that most Americans seem to rather like the idea of property destruction. If they did not themselves harbor a certain hidden glee at the idea of someone smashing a branch of their local bank, or a McDonald’s (not to mention police cars, shopping malls, and complex construction machinery), it’s hard to imagine why they would so regularly pay money to watch idealistic do-gooders smashing and blowing them up for hours on end.”

-David Graeber, On the Phenomenology of Giant Puppets

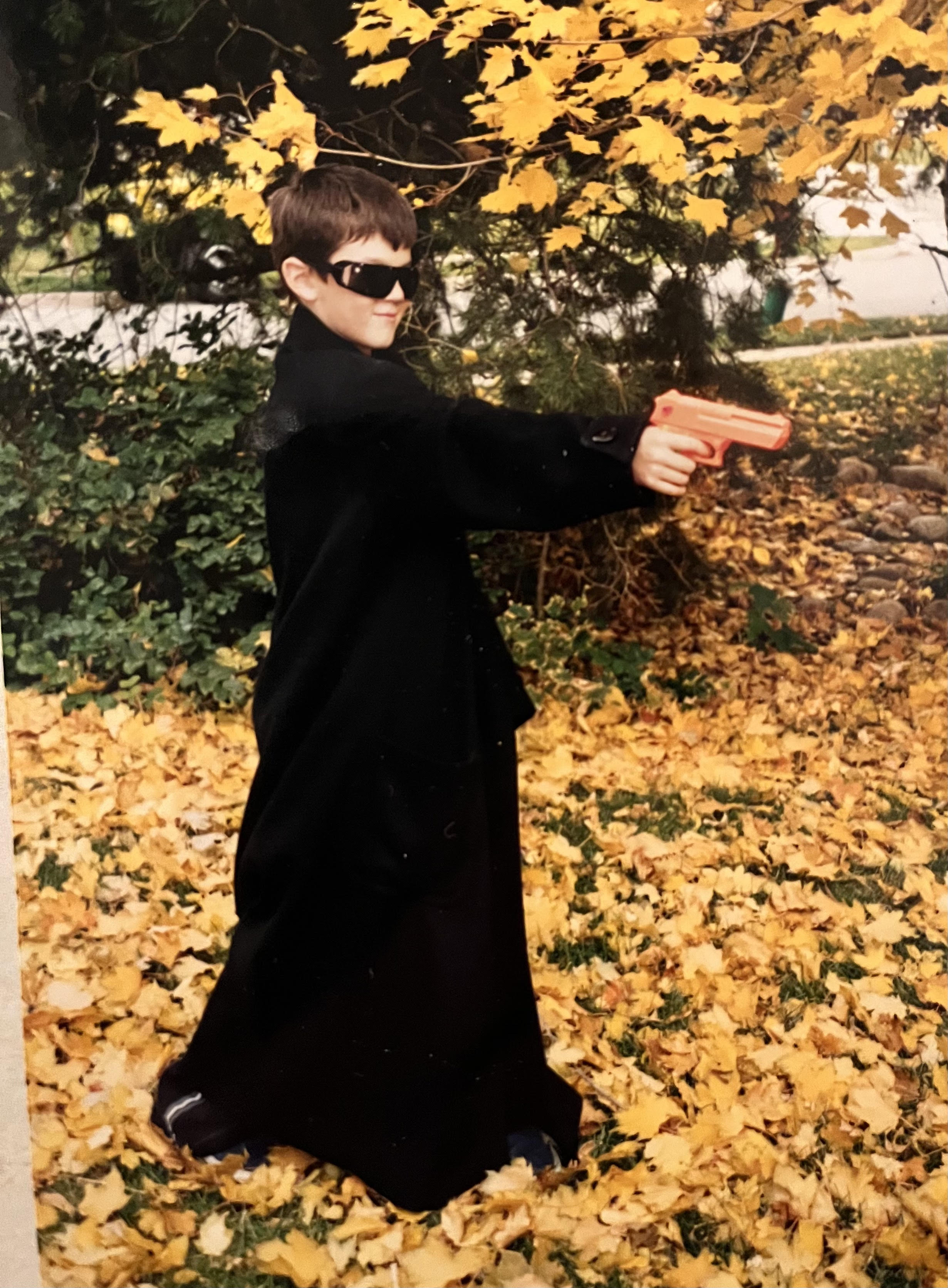

All good dystopian fiction can be interpreted as either a description of the present or a warning for the future, and while the most fruitful treatment of The Matrix must surely still be as a powerful, flexible, and metaphorical allegory, it’s rather stunning how much an entirely literal reading of the movie plays on the anxieties of life in 2021. Are we living in a simulation? Will A.I. pose an existential threat to humanity? I don’t believe these questions were being asked seriously in the public sphere when I first saw The Matrix, but then, I can’t really be sure what was happening in the public sphere at that time. I was ten years old, and I had to get special permission from my parents to see a movie with so much violence.

My friend Graham’s parents had to call my mom to convince her to let me watch an R-rated movie over at his house. It was probably the year 2000, a year after The Matrix had come out. “Yes, there are action scenes, there is some violence,” explained Graham’s dad over the phone, “but most of the action is beautifully choreographed martial arts, and it’s a thought provoking movie.” I think I appreciated the beautiful martial arts choreography at that age. I think I even appreciated the psychological character of the story. But the moments that really stuck with me most were the exploding helicopter! The lobby gunfight! Bullet time! Graham and I traded off turns being Neo as we pretended to gun down scores of cops and security guards.

I have a sense that in praising The Matrix, I’m supposed to downplay the degree to which it is simply a cool action movie, but I actually think this is central to what makes it so powerful. There are plenty of movies whose strong suit is some sort of cutting social commentary, and blockbuster action flicks are a dime a dozen. The fact that it did both of these forms—and did both of them well—reinforces the strength of the component parts. So yes, The Matrix is a big budget action movie, but it’s also a creative reinterpretation of a familiar form. At a time when action movie protagonists were mostly battling terrorists or Russians (or both), The Matrix asked “what if the fight scenes and explosions in an action movie were ultimately driven by the realization that you’re trapped in a system of domination and you have to fight your way out?”

If David Graeber is right, and the secret appeal for action movie audiences is getting the opportunity to revel in the destruction of the mundane environments of contemporary life, the Lethal Weapons and Die Hards that he writes about come with an inbuilt justification for indulging in this guilty pleasure. Even if our hero (almost invariably a spy or a cop) wreaks havoc in the process, he is ultimately defending the status quo, restoring a state of affairs in which we no longer have to fear that banks and shopping malls will be under threat of sudden and spectacular hi-def destruction. The Matrix does not offer this out to its audience. The movie begins with Trinity kicking the shit out of a room full of cops as they try to arrest her, and keeps that energy up for its entire runtime. If we enjoy the action on display in The Matrix it may be as simple as this: we really do relish seeing those office buildings explode.

2. Alienation and Exploitation

“The matrix is a system, Neo. That system is our enemy. But when you're inside, you look around, what do you see? Businessmen, teachers, lawyers, carpenters. The very minds of the people we are trying to save. But until we do, these people are still a part of that system and (the camera cuts to a shot of a police officer) that makes them our enemy.”

-Morpheus

The role of the police as enemies in The Matrix—enforcers of a system of domination they themselves do not understand—is so transparent as to be among the least interesting dimensions of the film’s social commentary. From the very first scene of the movie, the police are henchmen; brutish and bumbling armed thugs tasked with killing or arresting the film’s protagonists. They may be oblivious to their role in keeping people plugged into the matrix, but they carry it out nonetheless. Police officers are frequently depicted taking orders directly from the agents, and although Morpheus makes it clear that inside the matrix, anyone can transform into an agent, the line between cop and agent is particularly blurred as the one so frequently becomes the other.

But the critique implied by the movie goes far beyond the rather straightforward depiction of the role of the police in upholding the existing social structure, answering directly to the (in this case, robotic) ruling class. For sharper and more richly symbolic commentary, it’s worth looking at the movie’s treatment of alienation and exploitation.

The Matrix has a twofold dramatic rendering of alienation. First, we are shown the way that Neo has become so detached from his life as a computer programmer at a “respectable software company,” that his life has literally split in two. One life is lived in dingy apartments and basement nightclubs, while the other is inhabited by condescending bosses and sterile cubicles. Here The Matrix dramatizes an all too relatable condition, telling us, in effect, that our self-directed studies, our friendships, and our passions are so divorced from our experience in working life that we may as well be two entirely different people in these spheres*.

*Then again, for many of us this may not be a dramatization at all. How many in our subculture are surrounded by freaks in bondage gear in their nightlife, known by a name of their choosing, only to clock into a soul-sucking workplace the next morning with a supervisor that calls them by the name on their government ID? Again, the boundary between metaphor and reality collapses.

But then, the alienation in The Matrix runs even deeper than this. It’s not just on a personal level that you feel split in two, it's that everything feels just a little off. “You've felt it your entire life, that there's something wrong with the world. You don't know what it is, but it's there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad,” Morpheus explains. Again, the film holds up a (cracked) mirror to American life at the end of the 20th century. Do we feel something is wrong with the world, that we are detached from broader systems of structure and meaning in society, that forces outside our control impel us this way and that? The matrix is with you “when you go to work, when you go to church, when you pay your taxes,” and seemingly in all places where we may come to feel a distance between the popular justifications for our behavior (“I’m contributing to society”) and our feelings while engaging in this behavior (“did I choose this?”).

What, then, of exploitation? In what may be the most dramatic scene of the movie, Morpheus poses a question, “What is the matrix? Control. The matrix is a computer-generated dream world built to keep us under control in order to change a human being into this,” he answers himself, as he holds a battery aloft. The Matrix tells the story of a vast system that encompasses nearly all of humanity. People are born into it, most can’t conceive of anything else. This system has an intricate organization of violence to leverage against those that seek a way out, and those that run the system are fixated on destroying any enclaves of people outside of it. The ultimate goal of this system is to be able to harness the energy of everyone alive and leverage it to the benefit of those that run the system to the detriment of humanity writ large. To me, this sounds an awful lot like capitalism, though I think the power of the metaphor is that it is flexible enough to encompass relationships of structural exploitation of all sorts. There’s something palpable about the horrors of such a relationship, listening to Morpheus quantify the amount of energy that can be harvested from a human being as we are shown an infant hooked up to tubes and wires, steeped in a watery black liquid. And while I hesitate to assign too much meaning to Keanu Reeves melodramatically delivering the lines, “No. Stop. I want out! Let me out!” before collapsing into his own vomit, I do think this is an appropriate reaction to those moments when we see our world as it really is.

3. Acid Communism

“If the very fundamentals of our experience, such as our sense of space and time, can be altered, does that not mean that the categories by which we live are plastic, mutable?”

-Mark Fisher, Acid Communism (Unfinished Introduction)

“What is real? How do you define real?”

-Morpheus

British academic, theorist, and raver Mark Fisher was working on a book titled Acid Communism when he took his own life in January 2017. While the book will remain unfinished, an outline of his ideas survive in previous writings, transcripts of the final lectures he gave before his death, and a draft introduction to the book. Fisher had previously coined the phrase “capitalist realism” to describe a present in which for so many of us, “it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” Not only has capitalism positioned itself as the only system that is possible, he argued, but it has come to seem so inevitable, even natural, that it’s “no longer worthy of comment.” Acid communism, then, is a way of shaking free of the hold that capitalism has on our imaginations. It seeks to reveal the malleability of our world through psychedelia: strange art, ecstatic collective celebration, “genuinely new music—music that wasn’t imaginable a few months, never mind a few years before,” dreamlike fantasy stories, and, of course, LSD. It is a positive reappraisal of the potency of the sixties and seventies countercultural movements and a question about where those paths may have led were they not defeated or co-opted by the onset of neoliberalism. Faced with it being “easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” acid communism seeks to reintroduce “the spectre of a world that could be free.”

In a certain sense then, The Matrix can be read as an acid communist parable. Yes, it is impossible to imagine an outside to the system of domination in which we are confined, the film tells us, so much so that the system comes to be conflated with reality itself. The way that Neo breaks free from this illusion is through his connections in the countercultural underground which lead him along a trail of Alice in Wonderland inspired hints culminating when he takes a drug that reveals the literal plasticity of the world around him. This revelation, that the world as he has experienced it thus far is neither natural nor inevitable, drives him first to confusion and denial, but ultimately to the conclusion that he must risk life and limb in a mortal struggle against the prevailing social order.

It’s worth lingering on Alice and Wonderland here, as it is referenced extensively in both The Matrix and Mark Fisher’s incomplete introduction to Acid Communism. Neo’s encounters with Lewis Carroll’s fantasy world go beyond just following the white rabbit, and taking the red pill to “stay in wonderland, and [see] how deep the rabbit hole goes.” Much of the first half of the movie is a narrative and aesthetic allusion to Alice’s disorienting adventures. The checkered floor of the building where Morpheus offers Neo the red pill recalls the recurring patterned motif of wonderland, while the dilapidated Victorian furnishings are something of a cyberpunk rendering of Alice’s posh 1800s English environs. Neo, like Alice before him, goes through the looking-glass, being enveloped entirely by mirror-turned-liquid before awakening with a new realization about the cheap counterfeit that was his life up to that moment.

Fisher, for his part, is perhaps even more clear about the social critique implied by Alice in Wonderland, and is worth quoting here at length. Alice in Wonderland makes “the ordinary world appear as a tissue of nonsense, incomprehensibly inconsistent, arbitrary and authoritarian, dominated by bizarre rituals, repetitions and automatisms. It is itself a bad dream, a kind of trance. In [Alice in Wonderland], we see the madness of ideology itself: a dreamwork that has forgotten it is a dream, and which seeks to make us forget too.” Here, Fisher’s description of the acid communist dimensions of Alice in Wonderland reads almost as if it was written as a political appraisal of The Matrix. What is the matrix if not “a dreamwork that has forgotten it is a dream, and which seeks to make us forget too”?

Lewis Carroll’s work is an illustrative example of the type of culture that Fisher sought to highlight with acid communism. Carroll, despite his modern reputation and the otherworldly character of his tales, was never known to have used drugs himself, and for Fisher, psychedelia rather than psychedelics was the key. Beyond the substances, which art, which music, which culture, which experiences can denaturalize the existing state of affairs, and show us, as David Graeber has written, that “the ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently”?

“Another world is possible,” anarchists declared in the anti-globalization movement, culminating in the U.S. in 1999 when it was inscribed on the walls of downtown Seattle in a dramatic confrontation with the World Trade Organization—a world-spanning institution of suited, shape-shifting villains if there ever was one. Those that championed this slogan in the streets sought simultaneously to show that it was true. The form of the confrontation itself reveals the possibility of the world that is being struggled for, just as much in bullet time as in joyous, carnivalesque rebellion. And this, ultimately, is what I find so compelling about Mark Fisher’s line of thought just before his death and about The Matrix. The spark is not revealing hidden truths, it is demonstrating what else is possible. “I'm going to show them a world without you. A world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries. A world where anything is possible,” declared Neo at the end of The Matrix in theatres across the world in 1999, in resonance with his contemporaries.