April 2022

Nevada

A comrade and a friend wrote a wonderful book recently on the George Floyd Uprising. We decided to interview them about what’s in this book and their process and experience of writing it.

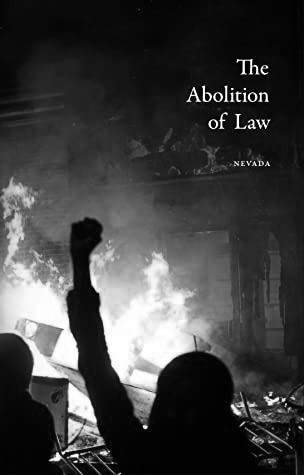

The Friends Print Collective is a print and design collective out of Minneapolis and St. Paul. They published and printed Nevada’s “The Abolition of Law.”

We encourage you to check it out. Copies of the book are available here.

1.[L&F] I suppose I should start by showing my hand and saying how much I truly appreciated the revolutionary thinking that went on within these pages. It felt refreshing, challenging, and simultaneously encouraging towards what Moten and Harney might call a revolutionary ensemble. Now that I have frontloaded my opinion, I’d like to ask you a few questions about your book, The Abolition of Law.

This book came out a letter you wrote titled “Warning” which was published by the Liaisons collective at The New Inquiry. I guess I am curious as to how thinkers work with an idea or a concept. How it moves and shifts throughout the different iterations of their study and how events – both internally and externally – can impact this process. Would you take a little time to help explain and orient us to what your process was like working with these thoughts over the last year plus? And in addition, how this thinking was particularly impacted by living in Minneapolis during the uprising?

[Nevada] First of all, thank you dearly for the kind words and I am glad to hear you got so much out of the book. Thank you as well for this opportunity to talk about it, I’m excited to get into it.

Yes, the first text I wrote for what would eventually become the analytical section of the book was “Warning.” But if you go back and read it—and this was even more true in the earlier drafts—it’s rather plainly responding to a practical issue that arose in the uprising. The issue was that the state had said the George Floyd uprising was ‘a bunch of white supremacists that were going to burn everyone’s house down,’ and overnight the uprising essentially ended. We can get more into the details later, and of course it’s all in the book. But I was pretty shocked by this sudden turn of events and was trying to figure out how it happened, but mostly I just wanted to tell people that it happened at all. At the time it felt like it was written months too late.

I continued to work on the text, to flesh it out conceptually, and draw connections to other thinking that had emerged from the uprising on a national level, like the work of Idris Robinson. It was at this point that I realized there was something deeper going on than a disinformation campaign or a simple counter-insurgency victory. The problem spoke to a struggle at the heart of the uprising between radically different visions of abolition. To put it simply, one vision offers us the same world, only a little less brutal, as the tasks of law enforcement have been distributed to a myriad of different departments with better reputations than the police. The other vision entails the abolition of not just a certain kind of law enforcement but of any law to be enforced—which would involve the complete transformation of life itself. And I continued to try and articulate the struggle between these visions, from a few different angles in a few different texts, which eventually became the book we’re talking about today.

So, it really couldn’t have happened without being a part of this uprising and experiencing it firsthand, from beginning to end, and attempting to pick up the pieces it left behind. I really like how Hannah Black describes this feeling: “Uprisings are the only time you ever learn anything new. Then you have months, or years, or decades of aftermath during which you have to keep drawing on the moment of rupture.”

Lastly, and this is crucial to say, is that I didn’t write this book alone. Of course, there are co-authors of certain parts noted in the book, anonymous or not, but it also was written from a place of collaborative study. Every word stems from conversations around dinner tables or bonfires, on walks or on porches. And some of them—like this one—took place over great distances. My name might be on the cover, but revolutionary thinking can never be reduced to any individual.

2.[L&F] In the introduction, you write about how the aftermath of revolt can run a risk of potentially becoming “frozen in time, unable to see past our nostalgia for such events as the world moves forward without us.” I wonder how we become passive voyeurs to the image of the past and in what ways nostalgia plays a hand in this process? Particularly, when those images of the past were forged by strong insurrectionary events. It’s almost as though past events lose their resonance with their revolutionary potential. Walter Benjamin’s concept Now-time seems to deal, at least in some form, with this problem of nostalgia.

But I am curious in what ways you think nostalgia hinders or deactivates potential for a sustained insurrectionary event? Or maybe said another way, how does nostalgia – in relation to the uprising – impact our capacities at recreating this historic rupture? How can thinking and being with each other move towards an eternal returning to the world and away from a frozen gawking at past insurrectionary moments?

[Nevada] At one point I made a joke to a friend that I almost included in the book. In discussing how the 2020 uprising will likely inform our thinking for the rest of our lives, I said “now I know what it feels like to be a ‘68er.” But this is a bit sardonic, because at this point we think of ‘68ers as being unable to look forward, to move beyond that single moment. If that’s what we become, then we’ll be just as irrelevant to the future generations.

But this doesn’t mean that past moments can’t inform our thinking. It was a strong insurrectionary event, as you say. To be honest, it’s hardly worth trying to describe the magnitude of it in words, nothing I can say could come close to capturing it. Of course, it will stick with us and we will return to it time and again. The line I quoted above from Hannah Black above illustrates this perfectly.

What I want to do is recognize the inherent danger lurking here, when we become too focused on what happened in the past that we miss out on what’s happening today. If we are too busy attempting to recreate our past experiences—an endeavor which will always fail—we will lose our chance to experience the present. I think this could be said of every generation of social movements. There will always be those who want to recreate the World Trade Organization protests in 1999, or to recreate Occupy Wall Street. These events will never be repeated, and we all chuckle whenever Adbusters announces their next big move. Trying to hold on to past events this way leaves us ill-equipped to perceive the present. Think of all the French commentators on the radical left who denounced the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) in 2018, and were left in the dust by the country’s most ferocious movement in decades. It didn’t look like the movements of the past and so not only were they unable to recognize its potential, they spoke out against it—at least at first.

With the cost of gas and food going up on Biden’s watch, I can only imagine that unrest will be at our doorstep any day now. And those of us looking for something just like what happened in 2020 will be sorely disappointed. Whatever happens will be monstrous, and it will defy every single notion of politics we still cling to. Yet we will have to jump into the fray regardless.

(An image taken from a sideshow.)

I don’t think I have a good answer for how we can “move towards an eternal return to the world,” or in Benjamin’s words, bring about “a real state of emergency.” I have written elsewhere on what could be called the “molecular continuation” of the uprising, such as how it manifests in sideshows, which I think is a really important in thinking about these ruptures in duration. And yes, our thinking and being together is also a form of that molecular continuation, even if it doesn’t always bear such a flagrantly criminal character.

3.[L&F] The first part of the book is composed of an interview with lundimatin and a firsthand account of the events of the uprising in Minneapolis. The second part focuses on the abolition of law. In the interview with lundimatin, there is a quote towards the end that struck me: “At the same time, it is decisive that we find ways to ensure that the movement is not transformed into a symmetrical armed conflict with the state, but I think many people know that. People have been fighting these fascist pigs for 500 years; there is a deep knowledge of resistance in America, and I think moments like this we really see just how smart and resourceful Americans really are.”

I really like this segment. By prioritizing difference, this fragment frames a communalized capacity towards revolt in a deeply affirmative and positive way. Those of us who were in the streets experienced a contingent ingenuity to think and act in a myriad of ways. It is crazy inspiring to see how dynamic and creative people were throughout the uprising as an autonomous response to their place and situation.

When the outcome isn’t exactly how we want it however, sometimes seems like we fall into – and by ‘we’ I mean those who choose to move into the streets – a sort of pessimistic nihilism. This quote shatters that nihilism and reorients us to difference and to joy by way of becoming a loose ensemble within revolt. I guess this isn’t a question as it is a statement. But please feel free to expound if any of it resonates with you or your ideas for choosing that piece as the opening interview to the book.

[Nevada] In his most well-known book, Black Marxism, Cedric Robinson writes extensively on what he calls the “Black Radical Tradition.” He defines it as “an accretion, over generations, of collective intelligence gathered from struggle,” from slave revolts that took place centuries ago up to present day. I think this emphasis on the affirmation of resistance—black resistance, specifically—is incredibly important, especially as it undermines the tendency to look back on uprisings or movements and judge them based on their “achievements.” I think that this happens because of the prevailing logic of politics, how everything is meant to fit into means and ends. But there is no telos, no demands to achieve or policies to enact. The George Floyd uprising was a means-without-end, to use Giorgio Agamben’s idea. This is what I mean when I wrote the line later in the book: “It is one thing to hold a sign that says, ‘redistribute the wealth;’ it is another to decide that all that shit on the store shelves is ours for the taking—and take it.

At the very end of section two in Black Marxism, Robinson wrote a short chapter on “The Nature of the Black Radical Tradition.” Here he reflects on the fact that the rebellions and uprisings that constitute this tradition have occurred with the notable absence of mass violence. Violence is of course an amorphous concept, but Robinson is attempting to make a point that there is a significant discrepancy between the tactics and forms of brutality enacted by the ruling class and those employed by the oppressed in their revolt. This isn’t an attempt to paint the history of black uprising as peaceful by any means—but simply that when given the opportunity, the enemy was not outright slaughtered.

There’s been a lot of chatter about armed struggle lately, which is often connected to—but not the same as—talk of civil war. However, armed struggle is a particular kind of resistance, defined not simply by the use of arms but by its fundamental symmetry. This notion of symmetry is usually used to note the dynamics that manifest as what is essentially a frontal clash between armies, but I want to dig a little further. There is also another level of symmetry—you have the subject of the guerrilla versus the state, also imagined as a subject. So even when this guerrilla war is “asymmetrical” on a tactical level, you are still stuck in this ontological symmetry that envisions victory as the military defeat of the state as a singular entity.

This is flawed in two ways: Firstly, it reintroduces means and ends, the political logic the revolt undermined as I described above. Second, the state isn’t simply the enemy. We are fighting the entire organization of the world, which is more than police and politicians. It also involves the infrastructures of the world, the arrangements of resources, and to bring us back to the book, our understandings of everything we take for granted, like the law. In Tiqqun’s words, “Empire is not the enemy. Empire is no more than the hostile environment opposing us at every turn. We are engaged in a struggle over the recomposition of an ethical fabric.” We are fighting over the definition of life, essentially, and that involves so much more than military victories.

Cedric Robinson is essentially arguing that this aversion to a certain form of struggle is a defining feature of the Black Radical Tradition, and I hope it’s not too imprudent to follow this hypothesis into the present. It may be worth noting that this slim chapter is Robinson’s first and only mention of the “ontological totality,” which would go on to be a key reference point for Fred Moten’s thinking.

(Graffiti seen in Minneapolis.)

4.[L&F] You talk about the early morning press conference that the governor of Minnesota held on May 30th, which subsequently followed the burning of the Third Precinct. During this ‘briefing’ the governor put forth a series of false claims that outside white supremacist agitators were coming into the Twin Cities to instigate violent riots. The lies were then parroted by the mayors of Minneapolis and St. Paul. The lies of course implying that the collective rage against the ongoing murder of black life is somehow unfounded, unwarranted, and not coming from Minneapolis.

In part II, titled Abolition, you identify this spreading of fear and false information as an almost defeating blow to the uprising in Minneapolis. I guess my question is, where do you feel this event leaves us in relation to the circulation and processing of information? This is obviously a very large question particularly when we consider the ways Russia and China seem to be cybernetically manufacturing public opinion. I am wondering if this is a larger strategic question concerning how rebels build networks of information sharing? And furthermore, at what point can we be able to identify and understand the endless limits that the state will go to in hopes of remaining in and preserving their power.

[Nevada] In the moment and its relatively immediate aftermath, the need for fact-checking seemed incredibly urgent. As with many of the tactical innovations seen in Hong Kong, there were a number of radical activists and militants around the country attempting to promote the emphasis rebels there placed on verifying info. Likewise, the infamous “The Siege of the Third Precinct in Minneapolis” includes an entire section describing fact-checking as a “critical necessity for the movement.”

In my writing, I don’t spend too much time on all the different rumors and conspiracy theories that were circulating at the time, but perhaps it’s a good idea to summarize a few. There were two main things happening, both that only really gathered steam after the press conference you mentioned. First of all, there were countless updates circulating social media about different things being on fire, like houses, libraries, etc. that were all untrue. People would see a tweet in all-caps about how this or that is burning down, and then check it out to find it totally untouched, or maybe the residents gathered around their backyard fire pit. The other thing was that there were tons of rumors of neo-Nazi gatherings and demonstrations. In one instance, a flurry of posts (many labeled “CONFIRMED”) described a KKK rally in a St. Paul park. But if you read the replies, people were posting timestamped photos of the same park, quiet and empty. In some of these rumors gone wild, it’s hard to even imagine what “kernel of truth” they sprung from in the first place, besides being an intentional disinformation campaign. But I haven’t done the research and don’t have proof of that, and I’m not sure it matters what percentage was intentional or relatively organic.

Having some distance from these events now, I’m not sure I still think of fact-checking as such a crucial thing. While yes, verifying information is quite important and we should do our best to avoid fear-mongering and inciting panic, I think we fall into the trap of trying to center some sort of universal rationality called the truth. I think it’s become pretty commonplace to accept that this is no longer compelling in our world—even "The X-Files” reboot covered this issue. And while this isn’t always the case, fact-checking can sometimes serve the function of the police.

On August 26th, 2020, Minneapolis police officers were pursuing a black man with a gun in downtown. When he was cornered, this man Eddie Sole Jr. took his own life. Yet all that the people observing the situation could see was the police advancing on a black man and that man with a fatal bullet wound. Nearly the same instant, fighting erupted and many windows in the downtown shopping district were being smashed to bits. The rest of the night felt like a brief repeat of the uprising a few months earlier, although with a much clearer emphasis on the de-centralized looting by car, as the street-fighting downtown did not provide as much of a center of gravity as the 3rd Precinct did in May. The next day, people again began to gather downtown, but before anything like the previous night could break out, prominent Leftist organizers arrived to tell people that the police did not kill Sole, and that they had no reason to be angry, and that they should go home. Overall, they were successful in defusing the tension that was building.

Of course, I want to be clear that the police did kill Sole, even if they didn’t literally pull the trigger. Yet here we are again, returning to these two visions of abolition: one where we shouldn’t be angry because the police were just doing their jobs, and one where the choice between prison and death is unconscionable.

There is something else we can see in the events of August 26th, though, and this goes back to your last question too. There were thousands of people who reflexively returned to the tactical and strategic basis of the George Floyd uprising. We’ve seen this again and again in the years since, as well, like in Brooklyn Center for example. So even if the counter-insurgency was able to halt the uprising in one moment, this legacy carries on to the next moment, and the next.

So, if I had a hypothesis to answer this strategic question with, I would say that we should openly and shamelessly affirm the actions of the uprising, to the participants of the uprising, rather than becoming an anarchist or communist Snopes. But yes, we end up at the same place, which is building networks and platforms to share information with others. Instagram story shares aren’t going to cut it. Do everything you can to break out of the algorithmic bubbles we are put in online, and above all get offline too. Print out zines, flyers, posters, put them everywhere you can, but also talk to people, talk to strangers, organize events that appeal to people other than your affinity group or political milieu.

I want to bring up one more point, in response to this question. It’s not only that the state manufactured this disinformation about these white supremacist outside agitators and everything stopped. How I see it is that they gave people this “out,” this way of excusing themselves from the situation that was otherwise terrifying for them. Urban liberals and leftists weren’t likely going to take up a mass project of auxiliary policing in the explicit defense of the white power structure. Yet by redefining the rioters as themselves the white supremacists, these people could then preserve both their culturally or ideologically woke positions while actively defending (often at gun point) the structures of white supremacy and capitalism. But I don’t think people rushed to defend this structure for ideological reasons like fighting fascists. I think they did it because the revolt was immense, and pushed them to their breaking point—and they chose to defend the existent rather than to leap into the unknown. As Saidiya Hartman once said, no one “wants to be as free as Blackness will make them.

5.[L&F] Towards the end of the book, you talk about the way policing and law show up in different often more insidious ways. As was the case with the ‘progressive’ ballots appearing to abolish the MPD and to eventually substitute it with a “Department of Public Safety.” You go on to say “The figure of the white supremacist agitator does not simply tarnish the memory and legacy of the revolt. It also illuminates the very stakes of the movement itself and its call for abolition does not simply mean the defunding of any specific department, as many activists advocate today. Nor does revolutionary abolition simply mean doing away with the brutality that police use to enforce the law, as offered by restorative justice. Instead, revolutionary abolition must mean the abolition of law, itself, along with the property relations that the law upholds.” Marcello Tari, in his book There is No Unhappy Revolution: The Communism of Destitution, talks about the difference between law and justice. How the former is nothing other than a continuation of the logic of domination and often friends fall into the siren song of institutionalizing potential into a form of governing power.

But I wonder what you imagine when you say the abolition of law. Many have a hard time envisioning what life could look like without law. Yet through Tari, Moten and Harney, and others one can begin to see a communal plane of ethical and justice-oriented living. Does this framing speak to what you imagine as a sort of escape from juridical thinking and being? That is, if we are to take Walter Benjamin seriously when he says justice is a state of the world.

[Nevada] You (and Tarì) are right to differentiate between law and justice, even if the latter has been so twisted as to be nearly as distasteful as the former. I think the same thing of “community,” which is an issue addressed in the second half of the book as well. Yet in the final pages I arrive at both “justice” and “community” in my attempt at thinking life differently, a life without law. Of course, it’s still barely a gesture at such a life, because such a life would be impossible to define in advance, and even if it were, I don’t think of myself to be in a position to describe it.

I mentioned earlier about paying attention to the molecular continuations of the uprising. I prefer to use the word ante-politics rather than molecular, taking the term from Fred Moten and those inspired by him, which is another way to describe the power or potential that has escaped capture so far or that has not yet been subsumed into the political sphere. I see sideshows as a really poignant expression of this; one of the most inspiring elements isn’t just their incredible tactical innovations but the ways in which they have developed ways of being together that don’t rely on police or the law because their existence depends on keeping the police at a distance. While it would be entirely possible for a new law to emerge from within this space (and this is exactly the problem much of my book tackles), what I’ve seen is precisely the opposite. My friend Jackson and I termed this “self-regulation” to illustrate how it differs from self-policing or the creation of a new transcendent law.

This isn’t to say that sideshows are prefiguring the world we wish to see, but that they offer, among many things, the ability to imagine ways of being together that don’t replicate the law. What happened during the uprising is that citizens, in taking up the call to fight the outside agitators, reintroduced policing in the same moment as they proclaimed to abolish the police. At sideshows, no one decides what is or isn’t allowed to happen. Sure, some people might provide feedback towards something they do or don’t like happening, and that feedback may indeed be forceful, but it never solidifies into a law. And certainly, no one will try to hand you over to the police because they don’t like what you did.

Lastly, on justice, I want to really emphasize how crucial the ideas of transformative justice are to this vision of abolition I’m advocating here. Transformative justice, of course, gets thrown around, distorted, and emptied of much of its content like many ideas in the activist lexicon. But I see it as a fundamentally abolitionist attempt to navigate justice outside of and without law. I cite the book Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement in the passage you quoted, which is a great anthology for thinking about transformative justice and abolition. To go further, I think we have to learn to translate these ideas beyond activist subcultures—which, despite its constant gestures to the accessibility, creates a highly insular frame of reference and vocabulary. Yet, as with my experience at sideshows and being a part of that subculture, the fundamental premises are not foreign to others and should not be treated as such.

(Minnehaha Liquors in Minneapolis on fire during the uprising.)

6.[L&F] The Abolition of Law has a beautiful and reoccurring theme of movement to it. You ruminate on the interplay of the idea of an “inside” and “outside.” A gorgeously ferocious line emanates from page 73 where you write, “To go further, we must investigate the material foundations of these measures – revealing that the myth of outside agitators is fueled by an inherent desire for a closed, stable social space. Yet the only thing preserving the notion of an ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ is a thin blue line.”

Saidiya Hartman, in a conversation she had with Fred Moten titled To Refuse That Which Has Been Refused to You, speaks on this sort metaphysical and material exchange. She posits, “Rather, I think the tradition is to produce a thought of the outside while in the inside. […] the thought of most folks is really devoted to this labor of trying to create an opening, which is often only discernible belatedly and it’s discernible as it becomes marked as crime or as it’s subject to a new form of enclosure that is the response to a certain kind of making/happening.” I guess what I am thinking about is the way colonialist methods within political economy set out to manufacture divisions between life on both internal and external levels, and how these divisions operate as a subjectivizing process towards civil thought. To which one eventually believes these divisions to be true and are what shape our relation to the world. As opposed to a sort of communistic thinking which orients an ethical relation to difference not as closure but as an extension of an ensemble.

Do you think it is helpful for us to frame thinking in this “inside” and “outside” dichotomy? I find myself balancing between the importance of it and also understanding that this framing – as you point out in reference to the rhetoric of the “outside white agitators” during the uprising in Minneapolis – seems to function as an abstraction from relation. As well, the larger material circumstances to how racism and bigotry occurs on an everyday level within this system and as the everyday function of this systemized thought.

[Nevada] Right—I think the dichotomy of “inside” and “outside” inherently limits our vision of what could be. I take it up only because this dichotomy has become the dominant framework we are offered to think about the world, but I take it up only to demonstrate its porousness to ultimately break it down. I’d like to think that I’m joining Saidiya Hartman in this project, if I understand her correctly.

That section was inspired by, again, what seemed to me as quite practical concerns but is ultimately based in this subjectivizing process and abstraction you’re talking about. For someone to “outside agitate,” there has to be an outside to come from, and for that to exist there has to be an inside that has an essential quality and is therefore inherently legitimate. This is problematic on a metaphysical level––Fred Moten’s thinking on enclosure and surround helps articulate this, but it’s also a problem on a simple geographic or material level.

First of all, it’s basically impossible to claim some geographic “inside” to the uprising. The Star Tribune mapshows damage stretching well past Minneapolis and Saint Paul city limits, with many incidents in first-, second-, and even a few third-ring suburbs. Even if damage was constrained to the city itself, this thinking would imply that by virtue of being a Minneapolis resident—or more specifically, having an ID that listed Minneapolis as your current residence—you were a legitimate actor in the uprising, and a Brooklyn Park resident was not.

I deal with this problem explicitly around George Floyd Square, which is the name given to the area where George Floyd was killed and the surrounding blocks, which for over a year remained barricaded to traffic and where a memorial and gathering space were created. This space and those who organized in it really exemplified this thinking, where residing on the blocks the Square occupied lent a legitimacy to your voice or project. But in reality, there was no consensus amongst the very diverse residents of the area, and plenty of people lived elsewhere or came from elsewhere to participate in activities or daily life there. But the discourse consistently employed did not match the reality—and it’s worth saying, I think this left many participants at the Square disadvantaged to handle conflicts between the many people who could claim this supposed legitimacy of living there.

Beyond geography, this also has to do with race. When we are not given a geographic interior as the source of legitimacy, we are told there is a racial interior. And this racial interior can only exist if being black, or being white, has unique, essential qualities, shared amongst everyone of that race. Despite how absurd this might sound, we hear it quite often in activist circles and beyond: center the most marginalized, amplify black voices, etc. While there are (usually) good intentions here, it offers us no possibility to understand the difference between the actions of a black rioter that throws a rock, and a black police officer that shoots them with a rubber bullet.

I want to be clear that in rejecting this racial “inside”, I am in no way denying that this uprising was unquestionably about black liberation. What I am trying to illustrate is that living in a certain city or neighborhood, or being racialized a certain way, does not guarantee any sort of solidarity with this vision of black liberation. (I follow this conclusion further in the next chapter in the book, on “race treason.”) This thinking instead becomes a serious obstacle because of how such false legitimacy is leveraged to defeat an uprising.

There is no inside or outside in an uprising. The only inside is “the fort,” to take up the image Fred Moten and Stefano Harney offer us in their opening essay to The Undercommons. The uprising only exists as the surround, “the common beyond and beneath—before and before—enclosure.” And what we surrounded was not only the 3rd Precinct but also white civil society as a whole.

Nevada is a writer and communist living in their hometown of Minneapolis.