October 2021

From Perilous Chronicle

Ryan Fatica

TUCSON, ARIZONA — When Frances Guzman didn’t hear from her son for two days, she knew something was wrong. She checked the Pima County Jail’s website and found that her son, Cruz Patiño Jr. III, 22, had been arrested July 30 and was being held in the county jail. She scheduled a visit for August 3 at 1:30 p.m.

“I scheduled that visit so I could make sure my son was okay,” Guzman said.

Just a few hours before her scheduled visit, Guzman got a call from a detective with the Pima County Sheriff’s Office, informing her that her son had been found unresponsive in his cell and transported to St. Mary’s Hospital. When she arrived at the hospital, doctors told Guzman that her son was on life support and was not expected to live. Less than an hour later, he was pronounced dead.

“When I was at the hospital the doctor had told me they were going to do everything they can to figure out what the cause [of death] is so I can have some comfort and peace,” Guzman said. “And I don’t have that comfort or peace.”

Since Patiño’s death, the Pima County Jail has reported the deaths of three more detainees, pushing the total number of people to die in jail custody this year to 9. In October, Sandra Judson, 71, and Jacob Miranda, 22, were both “found unresponsive” in their cells, and in both cases, sheriffs reported finding “no signs of trauma or suspicious circumstances.”

According to information released by the Pima County Sheriff’s Office and information gathered by a Reuters investigation last year, 2021 is now the deadliest year for the Pima County Adult Detention Complex since at least 2009 with one person dying in the jail about every 31 days.

In response to the uptick in deaths, the Pima County Public Defender’s Office is encouraging family members of those who died in the jail to file negligent homicide charges against the Pima County Sheriff who operates the jail.

“There is a serious lack of oversight and a serious lack of medical care going on at the bare minimum,” said Sarah Kostick, Supervising Attorney with the Public Defender’s Office. “Our office feels that it’s important that these people don’t die quietly.”

The number of deaths in the facility has risen this year despite a record-low jail population. As of Tuesday, the population of the jail was 1,697, approximately 150 lower than the daily average jail population in 2018 when 8 detainees died in jail custody in the entire year.

Cell #10 at the Pima County Adult Detention Complex where Cruz Patiño Jr. III spent his last days (Photo Source: Pima County Sheriff’s Office).

When asked about the deaths in the jail this year, Sheriff Chris Nanos said that although it’s his job to provide a safe jail environment, many aspects of the jail are out of his hands, such as the jail population and the privatized medical services. Medical services in the jail are overseen by the Pima County Department of Behavioral Health.

Nanos said that three of the detainees who died in the jail this year may have died from overdoses of methadone provided to them during their incarceration. “I know we had some overdoses that we were concerned about that were directly related to the administration of methadone,” Nanos said.

Paula Perrera, Director of the Pima County Department of Behavioral Health said that until recently, those receiving medication assisted treatment services, such as methadone, from Community Medical Services, a private opioid treatment provider, had been allowed to continue receiving those services during their incarceration in the jail. The department has recently begun to phase out that relationship and is transitioning all methadone treatment to the jail’s main medical provider.

“I believe that the way that methadone was being administered caused some concern and as a result of that we have modified how methadone will be administered in the facility moving forward,” said Perrera. “It is not accurate to say any deaths have been attributed to methadone overdoses. There are two events involving individuals who were receiving MAT [medication assisted treatment] services while in the [jail]… but there has been no confirmation at this time that those outcomes were due to methadone.”

Sheriff Nanos said that he couldn’t be sure methadone administration had led to the detainee deaths, but said that “if we see that there are repeated incidents of people who are seizing and collapsing after taking methadone, someone should be looking into that.”

Haley Horton, Regional Director of Operations for Community Medical Services in Southern Arizona, clarified that only one of the detainees who died in the Pima County Jail this year had been receiving treatment from their organization during their incarceration. That individual, she said, died of natural causes unrelated to methadone treatment. Horton could not specify which detainee she was referring to due to privacy considerations.

She also specified that the relationship between Community Medical Services and the jail had not yet ended. The relationship, she said, was in the process of ending only because the new jail medical provider, Naphcare, was willing to provide medication assisted treatment for opioid use disorder, whereas the previous provider had been unwilling to do so. “The new healthcare provider asked if they could take it over and we were happy for that to happen,” said Horton. “We don’t really care who provides it, we just really like to offer medication assisted treatment to those individuals with opioid use disorder. Their risk of overdose at the time they are released is less.”

Nonetheless, Kostick, with the Public Defender’s Office, says her office believes the sheriff isn’t doing enough to prevent deaths in the jail. Attorneys with her office plan to go with the families of those who have died in the jail to the Pima County Attorney’s Office to formally file criminal complaints against the sheriff in the coming weeks. “We have three or four families who are interested in filing charges in addition to whatever civil remedies are possible,” she said.

“Now obviously, whether charges are formally filed is up to the Pima County Attorney’s office,” said Kostick. “We hope the County Attorney’s Office takes notice and wants to take action.”

Joe Watson with the Pima County Attorney’s Office said that he could not comment on how his office would respond to the potential criminal complaints. However, he did say that the county attorney is paying attention to the deaths in the jail. “We are certainly aware of the number of deaths in the Pima County Jail in 2021 and we find it alarming and disturbing,” he said.

By all appearances, Laura Conover, the Pima County Attorney, is taking a much different approach to her relationship with the Pima County Sheriff. Last month, Conover co-wrote an op-ed for the Arizona Daily Star in collaboration with Sheriff Chris Nanos and Tucson Police Chief Chris Magnus mixing tough-on-crime rhetoric with calls to reduce the jail population.

Earlier this month, lawyers with the Public Defender’s Office met to decide how to respond to the spate of jail deaths. Initially, they decided to reach out to the sheriff’s office directly. The response, said Kostick, was “unsatisfactory.” It was “the standard ‘we’re looking into it, we’re concerned’ line,” she said.

The rise in deaths comes as the jail transitions from one privatized medical care provider to another. In June, the county’s contract with Centurion Detention Health Services expired and the company decided not to offer the county the option of extending the contract. In response, the Pima County Board of Supervisors announced that Centurion was in breach of contract and quickly signed a one-year contract with Naphcare, a nationally based provider of carceral medical services. That contract was approved by the County Board of Supervisors September 7 and took effect October 1, according to the sheriff’s office. The new provider, Naphcare, is charging more than $500,000 more per year than Centurion.

Neither Naphcare nor Centurion responded to requests for comment.

At least two of the deaths in the jail this year were attributed to “natural causes” by the Pima County Medical Examiner, including the death of Cruz Patiño Jr. III. “Natural causes” is a blanket term for any death not caused by active intervention from an outside force, such as accident, homicide or suicide.

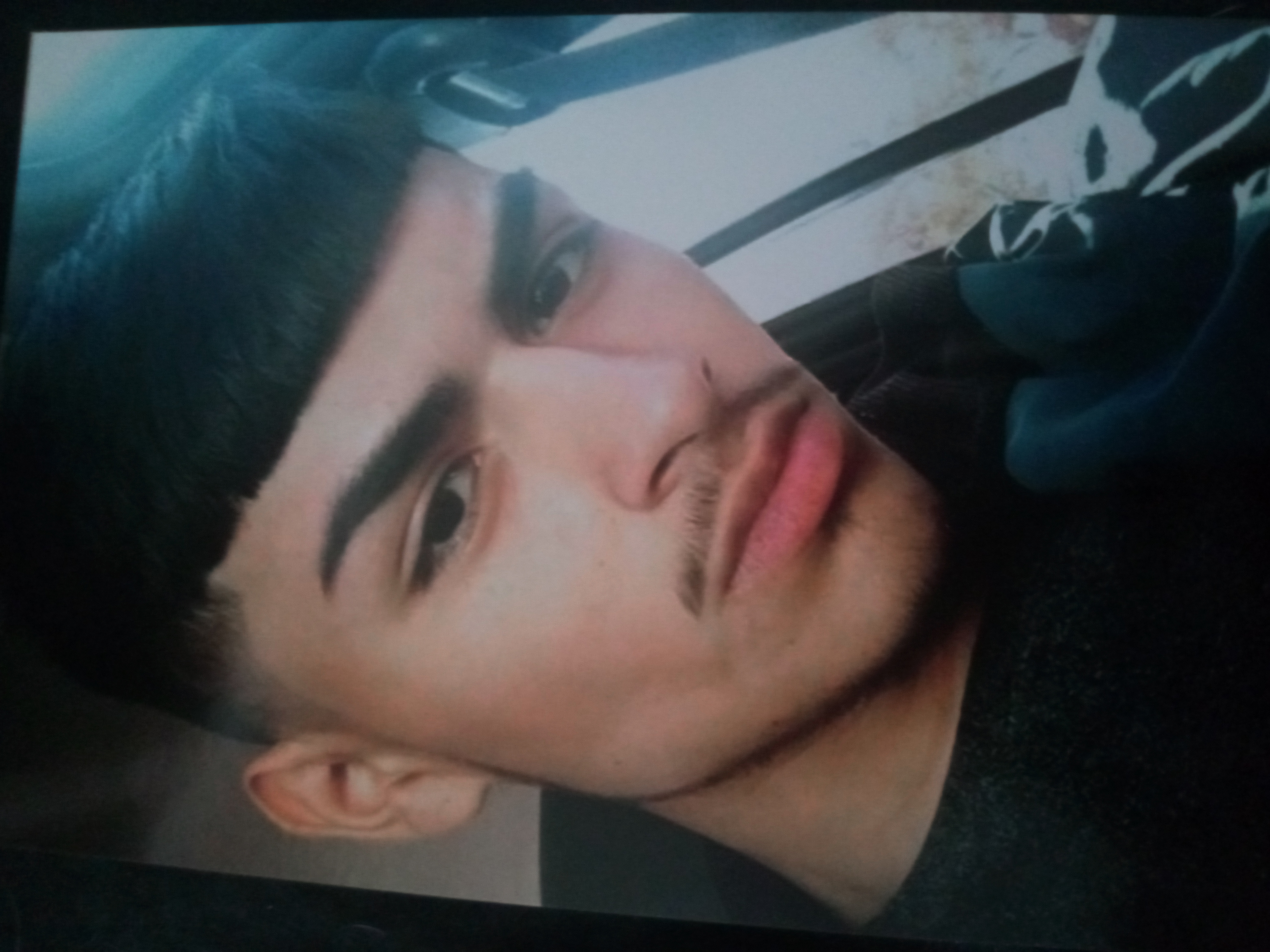

Cruz Patiño Jr. III, 22, died in the Pima County Jail August 3. (Photo Source: Frances Guzman)

According to Dr. Gregory Hess, Chief Medical Examiner for Pima County, his office’s autopsy procedure does not determine whether deaths were caused by things like medical neglect or conditions of confinement.

“We’re just the cause of death folks,” said Hess. “We tell people what happened as factually as we can. So when people have questions about standard of care and whether things were done correctly, people can have those questions but it’s not usually us who’s opining about it.”

According to Nanos, one of the main problems is that the jail population is too high. Many of those who are booked into the jail each year, Nanos said, should not be there. “My belief is that we have individuals in the jail who are there for nonviolent crimes who shouldn’t be there. Jail is a bad place for bad people. Because you have a drug habit, a drug addiction or suffer from mental illness, jail is not the place for you. Hospitals are for people who are sick. Jail is for bad people.”

Nanos is not proposing letting people go free, but would like to expand the use of electronic surveillance methods to shift the department’s custody of detainees outside the jail and into the community. “It costs $127 a day to house somebody in that jail,” Nanos said. “That ankle monitor costs me $15 a day. You tell me which is wiser. I can know where you’re at every second of the day with that monitor.”

In a statement provided to Perilous on the recent rise in jail deaths, the Southern Arizona Chapter of the National Lawyers Guild called the situation at the county jail “criminal.”

“We’re seeing the jail population rise rapidly, approaching pre-pandemic levels, even though crime rates aren’t rising,” the group said in their statement.

The guild called on Laura Conover, the Pima County Attorney, to do more to reduce the jail population. “The most immediate step that can be taken to reduce harm to the community would just require the County Attorney to follow through on her campaign promises to reduce the number of cases where the prosecutors are seeking to hold people on bond,” the statement reads. “She can also refuse to prosecute petty cases, from simple drug possession to ‘dirty house’ cases. She can, as other ‘progressive’ prosecutors have done, refuse to prosecute pretextual traffic stops. All of those actions would be simple, immediate steps that might save lives.”

Those who died in the Pima County Jail this year are:

· January 18: Jesus Aguilar Figueroa, 70

· January 21: Norberto Medican Beltran, 47

· May 31: Justin Crook, 29

· June 4: Jack Dixon, 29

· July 21: Weldon Ellis, 55

· August 3: Cruz Patiño , 22

· September 25: Zachariah Farrington, 42

· October 9: Sandra Judson, 71

· October 11: Jacob Miranda, 22

The Death of Cruz Patiño Jr. III in the Pima County Jail

Frances Guzman, mother of Cruz Patiño Jr. III, holds a photo of her son who died in the Pima County Jail in August (Photo Source: Perilous Chronicle)

Cruz Patiño Jr. III was arrested July 30 in the Safeway parking lot at East Golf Links and Wilmot on Tucson’s east side. He had several outstanding warrants for misdemeanor violations including trespassing, shoplifting and one felony charge for third degree burglary, so police booked him into the Pima County Jail.

According to Guzman, Patiño was addicted to opiates and didn’t have a stable place to live at the time of his arrest. Like many people, Patiño got addicted to pills after a bad car accident about 5 years ago led to chronic pain. “He got into an accident and he decided to go the other route instead of getting physical therapy and all that,” said Guzman. “His back was always hurting him.”

When Patiño was booked into the jail, he was immediately placed on detox protocols and given medicine to assist him in coming off opiates. Jail records do not show that Patiño was being treated for any other illness during his time in the jail.

After his death, the Pima County Medical Examiner performed an autopsy on Patiño’s body and determined that he had died from necrotic pneumonia—an uncommon and severe complication of bacterial pneumonia—however Patiño’s family reports that he was not sick on the day of his arrest.

“He didn’t have a cough and I know that my son would tell us if something was bothering him,” said Guzman. “My son’s never had pneumonia or any problems like that.”

Medical records from the jail show that Patiño was taken to the medical unit in a wheelchair at approximately 6 p.m. the night before his death after being found “unresponsive” in his cell. He was examined by a Centurion nurse, who wrote in her notes that Patiño was able to answer questions and seemed oriented. Her notes do not indicate whether she listened to Patiño’s lungs or checked his oxygen levels.

“Pt is responsive to loud voice, he is able to sit up, scoot back in the wheelchair,” the nurse wrote, according to jail medical records shared with Perilous Chronicle. “He answers questions appropriately, Oriented x 3, was able to say what he is detoxing from and expresses his symptoms without difficulty. VS [vital signs] are stable with a BP [blood pressure] of 94/72 generally runs low 100s over 70s HR [heart rate] 79.”

Cell #10 at the Pima County Jail where Cruz Patiño Jr. III slept on a mattress on the floor (Photo Source: Pima County Sheriff’s Department).

Despite being examined by the nurse and determined ready to return to his cell the evening before, Patiño was found “unresponsive” at approximately 5:55 a.m. the next morning. Jail staff were alerted to his condition by his cell mates who banged on the cell door, demanding Patiño receive medical attention. Patiño was given CPR by medical staff, who also administered naloxone–an opiate overdose reversal drug.

Patiño was rushed to St. Mary’s hospital where he was pronounced dead at 11:26 a.m. “It was a nightmare,” said Guzman.

To Sheriff Nanos, Patiño is an example of someone who never should have been in the jail in the first place. “Mr. Patiño, 22-years-old, basically got a death sentence because he was sentenced in there for all these misdemeanor warrants,” said Nanos. “Misdemeanor warrants with a $250 bond. It could have been a $10 bond and he couldn’t have paid it. He didn’t have $10 to his name.”

Court records show that in January, 2021, Patiño was arrested with a friend outside a home and charged with burglary for allegedly breaking into an outdoor laundry room. According to a statement from Patiño’s co-defendant in the case, the two were using drugs and were hungry and broke into the laundry room which contained outdoor food storage.

Patiño did not live long enough to go to trial in the case, but his co-defendant accepted a misdemeanor plea shortly before Patiño’s death and was released on probation.

Beth Wiese, a harm reduction advocate with the Church of Safe Injection-Tucson and a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Arizona in the neuroscience program, pointed out that jails are often used as de facto detox centers, despite the fact that they are not actually designed to fulfill that role. “Jails are inhumane to begin with,” Weise said. “It is absolutely disgusting that people are held against their will in such conditions, and even worse when they are experiencing symptoms of withdrawal.”

“Punishment doesn’t solve problems,” Weise added, “it only makes folks better at hiding things. Access to resources are what people need if society really wants to get to a place where the problem is resolved.”

Guzman is represented by Lisa Kimmel, an attorney with Goldberg and Osborne who is investigating Patiño’s death. Although Kimmel is gathering information for a possible lawsuit, she says she has not yet filed a civil action in the case. “We’re still at the beginning stages of our investigation. We’re not at that stage yet.”

More than anything, Guzman seemed to want the world to know that her son was a good person who didn’t deserve to die. “He had his issues, he’s human, but that’s my love, that’s my son,” said Guzman. “He was a loving brother and uncle. We miss him.”

Ryan Fatica is a member of the Perilous Editorial Collective and a founding member of Perilous Chronicle. He is based in Arizona.