JUNE 2020

From Blind Field

Wren Awry

The stairwell that led to ABC No Rio’s second-floor kitchen was dim and dusty and, as I made my way up it, my worn high-tops kicked at brightly-painted plaster fallen from the mural-covered walls. But at the top of the stairs, sunlight streamed through the kitchen window and illuminated the landing. My friend Sebastían and I stepped across the threshold and into the kitchen, where a table piled high with dumpster-dived vegetables and donated bags of bread was surrounded by a half-dozen volunteers. The year was 2006 and we were both seventeen-years-old, two queer kids who attended Catholic school in the nearby suburbs and took the train to the city on the weekends to go to punk shows and protests. We volunteered with Manhattan Food Not Bombs at ABC No Rio–a radical social center housed in a Lower East Side tenement from 1980 to 2016–every other Sunday throughout that school year.

“Mold is usually fine to just cut off,” Stasia, who bottom lined the free meal offered each week in nearby Tompkins Square Park, told us the first time we volunteered. “But some people are allergic to it and we won’t know, so compost the whole thing,” she added. She picked up a tomato flecked with fuzzy green and held it out to us as an example before adding it to a bowl of scraps, which would ultimately be turned into a rich humus to coax flowers, peppers, and herbs out of the soil at one of the nearby community gardens. She showed us how to rinse off vegetables in a bowl of cold water and brush away lodged dirt, then pointed us to a pile of knives and cutting boards.

As we peeled and diced, the other volunteers told stories. Most of them were five to fifteen years older than Sebastían and I. They talked about where they lived across the river in Brooklyn, in squatted buildings with fantastic names like the Batcave, and reminisced about the 2004 Republican National Convention: some rode as part of the 6,000-strong Critical Mass bike ride while others were part of a lawsuit that wouldn’t be won until 2014, seeking amends for the hundreds of RNC protesters held at a bus-depot-turned-holding-facility without processing for over twenty-four hours. They also spoke of the fight to save the Lower East Side’s community gardens, which was ongoing but had come to a fever pitch a few years earlier, at the turn of the millennium. Then coalitions occupied and defended spaces like El Jardín de la Esperanza on East 7th Street, where they locked down inside a giant coquí in an attempt to stop bulldozers from knocking down vegetable patches, grapevines, and the garden’s casita.

Years later, I became interested in stories of food-related mutual aid–reciprocal community care that prioritizes solidarity over charity, and is often eclipsed by the equally necessary but more pointedly disruptive work of street protests and direct actions. As I dug into the topic, I realized that the Lower East Side teemed with histories of radical food sharing and places where growing and preparing meals intertwined with resistance to capitalism and the state.

*

Toward the end of the 19th century, “American abundance was so staggering that the garbage that accumulated daily in cities like New York could support a shadow system of food distribution operated largely by immigrants,” Jane Ziegelman writes in 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement. “The rag-picker was a key player in this shadow economy, redistributing her daily harvest to peddlers, restaurants, and neighborhood groceries. In her own kitchen, the rag-picker’s culinary gleanings formed the basis of a limited but nourishing diet.” By the 1880s this job was typically done by poor and working-class women who immigrated to lower Manhattan from southern Italy. Middle-class New Yorkers–the descendants of earlier generations of immigrants who had settled in Manhattan, on occupied Lenape land–reviled ragpickers, but their work digging through upper-crust trash bins allowed these women to feed their families and communities. Cabbage and onions went into soup, tomatoes were bartered for macaroni, and leftover citrus was cooked into sweet-bright marmellata. The gleaning traditions Italians brought with them from their agricultural hometowns allowed them to make sautés and broth with ciccoria, or dandelion greens, harvested each spring from empty lots across the city.

In 1883 the gleaners were considered “the lowest of the low, and yet they seem to be as happy as their neighbors and social associates,” as The New York Times marvels in an article, unaware of what the women who made up the bulk of this occupation must have known: That there was more food available in Manhattan’s waste bins than in the wheat fields and olive orchards they left behind in Mezzogiorno; that it was greed, not scarcity, that drove hunger in this “land of bread and work.” This remains true today: up to forty percent of the U.S. food supply goes to waste annually—unsold, spoiled, or left to rot in landfills because it’s blemished or to keep prices high–and even before demands for aid skyrocketed due to the impacts of COVID-19, over 14% of NYC residents experienced food insecurity each year.

*

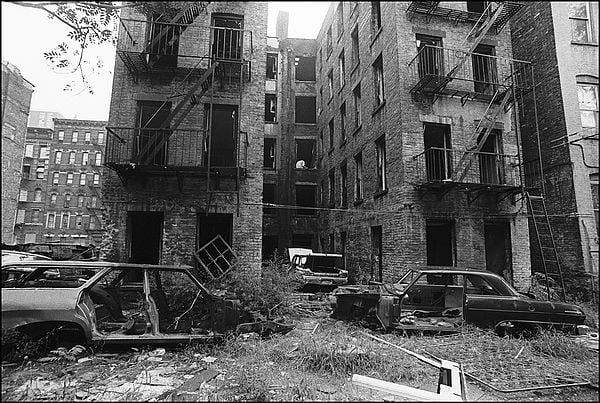

At the turn of the 20th century, the Lower East Side was the most densely populated neighborhood in the world, but by the 1970s that population had dwindled. Industrial decline and fiscal crises were followed by planned shrinkage: the intentional withdrawal of city services from fire departments to libraries in communities deemed unable or unfit to survive, a decision that was invariably racist and classist in nature. Landlords, left with half-empty high rises or rents that couldn’t be raised, torched buildings for insurance money, leaving a landscape that Malve von Hassell in her book The Struggle for Eden: Community Gardens in New York City likened to “abandoned lots and crumbling buildings and vacant lots giving it the appearance of a blackened slab of Swiss cheese.”

Neighborhood residents—many of whom were part of an upswing in Puerto Rican migration to the city in the 1940s and 50s—began clearing abandoned, rubble-strewn lots and turning them into gardens. These gardens were frequently born out of community cooperation: La Plaza Cultural, started by activists from Latinx-led organization CHARAS, worked with Liz Christy of the group Green Guerillas, who scattered seed bombs and planted willow and linden trees; while Carmen Pabón, a self-proclaimed “social worker without a license” who painted, wrote poetry and collaborated on street theater about corrupt housing policies, worked with houseless community members to found Bello Amanecer Borincano Garden in 1984. While the gardens abounded with fruits, herbs, and vegetables, they also functioned as crucial community gathering spaces: Pabón used Bello Amanecer Borincano as a base from which to distribute food and clothing, and housed families who needed a place to stay in the plot’s casita; La Plaza Cultural doubles as a performance space and, for a time in the late 1980s, housed a tent city and soup kitchen.

Starting in 1978, New York City’s gardens were semi-protected by “Operation Green Thumb,” which legally recognized the autonomously-built green spaces. However, gardens were considered a “temporary use” of space and leases were easily canceled. Miranda J. Martinez, in Power at the Roots: Gentrification, Community Gardens, and the Puerto Ricans of the Lower East Side, notes that, “the land could be sold for development without consultations with gardeners on site.” By the early 1980s gentrification had begun, driven, in part, by artists moving into the neighborhood, many of whom were of white, middle-class backgrounds. “Art that incorporated urban blight as an aesthetic theme effectively helped to market the Lower East Side as a new bohemia,” Martinez writes, “New investment and a new class of residents began to move in.” Many of these newcomers were drawn by developers who refurbished old buildings and marketed them as cheap living and studio spaces. By the 1990s garden land became desirable for housing developments and–particularly under Rudy Giuliani’s tenure as mayor– they were targeted for removal.

During that same decade, a movement sprouted to defend gardens threatened by development, including El Jardín de la Esperanza, originally founded by Alicia Torres in 1978 and run, for the next twenty-two years, by a group of community activists, many of whom lived in the tenant-managed building next door. In its prime, Esperanza overflowed with flowers, vegetables, grapes, and the sound of people gathering in and around the casita that anchored the space, but by 1999 the land had been sold to developer BFC Partners. Donald Capoccia, a principal in the firm, had a reputation for razing gardens and wanted to build an apartment building—80% luxury housing, with only 20% reserved for working-class residents—on the site. A coalition formed, including members of other gardens, activists from Times Up! and Reclaim the Streets, and squatters who occupied abandoned buildings across the Lower East Side. While some fought for Esperanza in the courts, others took direct action, installing sleeping dragons and other lock-down devices in the garden, including one in the shape of a sunflower. From late 1999 to early 2000, garden defenders kept vigil from the giant canvas-and-mesh coquí, a frog endemic to Puerto Rico and symbolic of the island, perched on Esperanza’s fence. In a 1999 article for the Village Voice by J.A Lobbia, Alicia Torres’ son Jose said, “There are many myths about the coquí in Puerto Rico, and one is that a monster came stomping through town one night terrorizing people …” and the tiny coquí with its big cry was the only animal able to deter it. “A coqui is tiny, but it got rid of the monster,” Arish, a garden defender, continued, “We gardeners are tiny, but we want to save the garden by making a lot of noise.”

While many gardens still punctuate the Lower East Side, El Jardín de la Esperanza was among those that were ultimately lost. On February 15, 2000—two hours before a temporary restraining was handed down to halt the destruction of any Green Thumb gardens—bulldozers arrived at Esperanza. After removing locked-down protesters and arresting thirty-one people for resisting arrest, criminal trespass, and obstruction of government process, the bulldozers leveled the rose bushes, arbor, casita, and lovingly tended vegetable plots. The rooster that lived in the garden was safely removed shortly before the destruction began.

*

On those Sundays in 2006, Food Not Bombs would finish cooking by the early afternoon. We loaded the trays of salad and pots of soup into shopping carts and wheeled the food a mile away to Tompkins Square Park, weaving past many of the gardens I heard about around the prepping table and would, years later, read about in greater detail. Vines cascaded over gates, splashes of orange daylilies lined pathways and, passing the 6th Street & Avenue B Community Garden, I’d peer up at Eddie Boros’ 65-foot toy tower, made of recycled treasures and planks of wood. A block-and-a-half past the garden, we turned our carts left and entered Tompkins, the noisy green heart of Lower East Side counterculture and resistance.

Unlike many soup kitchens and food pantries, Food Not Bombs groups see their meals as a form of direct action against capitalism’s waste, government spending on militarization instead of nourishment, and the criminalization of sharing food in public spaces. “It is the Food Not Bombs’ position that we have a right to give away food anytime, anywhere, without any permission from the state,” write Keith McHenry and C.T. Lawrence Butler in the book Food Not Bombs.

McHenry and Butler were part of the first Food Not Bombs collective, founded in Massachusetts in 1981 as an outgrowth of the anti-nuclear movement. Since then, activists have repeatedly been shut down, fined, and detained for sharing food. San Francisco was a frequent site of these interruptions, most notably when fifty-four volunteers were arrested on a single day in 1988 in Golden Gate Park. “After the police have left the area bring out more food but still leave some hidden so if the police come back you will still have more to serve,” reads step two of a how-to entitled “If the Police Start Taking Your Food” included in Food Not Bombs, while step three assures the reader that, “Very rarely do the police come back a third time because they are already feeling very foolish by the second time.” Although Manhattan Food Not Bombs has seen its share of police busts–part of a longer history of resistance and repression in Tompkins Square Park–throughout the year or so I volunteered, we were never disrupted.

Young and eager, Sebastían and I did whatever we were asked once we arrived at the park, which sometimes meant laying out zines or handing out bread, and other times ladling hot soup into bowls–I was careful not to spill and shyly mumbled a response when the diners offered up a thank you. These were often houseless community members who spent their days in Tompkins, chatting and playing chess or music, although everyone who wanted to was invited to eat or volunteer to prepare the meal. This was a pushback against church or city-based programs that demanded faith or proof of economic hardship in exchange for food and created sharp distinctions between those receiving and giving aid.

After everyone was served and the crowd dwindled, I filled my own bowl, dipping bread into a lentil soup or ginger-laced curry Stasia had cooked up with whatever was donated that week. As I ate, I looked out over the park: the tree-lined avenues, the lawn where train hoppers hung out all summer and the park benches designed, so the rumors went, with armrests placed close together so people couldn’t stretch out and take a nap.

*

In 2019, I took a tour of Tompkins with Bill Weinberg, a writer who works with the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space. I scribbled notes anytime he mentioned the radical food history of the park and later, by parsing through books and newspaper articles, and created a sort of mental map.

A relief garden was planted in Tompkins during the Great Depression. Thousands of children were issued four-by-four plots to plant vegetables and harvests were equally divided. Nearby, soup kitchens were set up at newly formed Catholic Workers’ Houses of Hospitality, borne from a Christian anarchist movement centered on voluntary poverty, prefigurative politics, and works of mercy.

“The famous Digger stew, which is made daily in a huge white-enameled pot in a kitchen behind the office, is ladled out—free, of course—to anyone who wants it every afternoon around five o’clock in Tompkins Square Park,” reads a New Yorker “Talk of the Town” article from 1967 about a faction of the theater-centric anarchist group that made the Lower East Side home in the 1960s. “When Clyde, Susan, Diego, and Richie are asked to explain why they are performing these services for the lower East Side community, each repeats the enigmatic Digger motto: ‘Diggers do.’” The Diggers saw sharing free food as a way to teach people about their anti-capitalist ideals, and in San Francisco diners had to walk through a large wooden “Frame of Reference” before they were served.

Formerly a settlement house for recently-arrived immigrants, the Christodora at 9th and B was home to chapters of the Young Lords and the Black Panthers in the 1960s, and both groups ran free breakfast programs for children. One of these programs, run by the Young Lords on the Lower East Side, fed about twenty-five children each school day. “The reason that the YLP has these free breakfast programs is that many of our children go to school hungry every day,” reads an article from the newspaper Palante published on July 3, 1970. “In order for us to have a thinking mind, we must have a full stomach. Free Breakfast Programs will not change the racist, brainwashing education system in this country, but they do deal with the immediate physical needs of our people.”

St. Brigid’s Church, located a block from the Christodora, was built by Irish immigrants fleeing the Great Hunger of the 1840s and nicknamed “the Famine Church.” Over a hundred years later–during what Weinberg calls the Class War period, which stretched from the late 1980s to early 1990s and began with a pitched battle in the park between homeless activists, anarchists, and the police — students at St. Brigid’s School brought food to people occupying Tompkins in tents. Leftovers from the school’s lunch program were legally supposed to be thrown away so, as Pastor George Kuhn told Clayton Patterson in an interview, the cafeteria workers would “put the unused food in a marked black garbage bag that they put out as trash” and he would collect and distribute it. Once, Kuhn crossed a police line with other religious leaders to deliver food to activists occupying an abandoned school and, when the police said that they were under orders to not let anyone through, he replied: “I’m following orders too. To give food to the hungry and drink to the thirsty.” The ministers crossed the line, hoisted up the food on pulleys, and were arrested.

*

These days I live across the country and I last visited ABC No Rio on a Sunday in 2018, a year after the building was bulldozed. Peering through the construction hoarding, I found an empty lot: ailanthus and knotweed sprung up where the tenement’s foundation once lay. An orange boom lift pointed upward a few yards from where the stairwell once stood, and I imagined walking up those dimly-lit steps into the kitchen where I first learned the value of mutual aid. I imagined picking up a knife and crushing garlic under the flat side so many times that its pungence sunk into my hands and stayed there for days, and listening to the other volunteers tell stories that suggested another world was possible.

I know that spaces created outside of or in resistance to capitalism are often ephemeral. In the case of ABC No Rio, the collective has fundraised millions of dollars to put a new, building-code-approved structure on the lot—models show a tall, sleek structure built to maximize space and the possibilities of alternative energy, with vines cascading down the façade—but ground hasn’t broken yet. In that moment, standing in front of the emptied lot, the world felt a little more tenuous than usual, a feeling underscored by the scent of coffee wafting down the block from a new, three-dollar-a-cup café. But later that same day, I walked through the Lower East Side, by the community gardens and through Tompkins Square Park. Past the dog park and the green lawn where hipsters had replaced train hoppers, I saw a folding table filled with soup, bread, and salad. The volunteers behind it were busily ladling out bowls, and a banner reading “Food Not Bombs” hung off the front: a reminder that some things, after all, remain.

This spring, as COVID-19 reached the United States and hit New York City particularly hard, I asked friends if Food Not Bombs had continued serving in Tompkins despite the pandemic. “I heard it was still happening as of a week or so ago,” one told me in early April, then added that food-related mutual aid projects were proliferating in the city, as they were in so many other places. In the midst of crisis, neighbors and collectives around the world set up ad-hoc grocery delivery services and safely prepared meals for one another, insisting on food-sharing as an act of radical care.

Bibliography:

“A New Building.” ABC No Rio, http://www.abcnorio.org/newbuilding.php#.

Belasco, Warren James. Appetite for Change: How the Counterculture Took on the Food Industry. 2nd ed., Cornell University Press, 2006.

“The Baldizzi Family.” 97 Orchard: an Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement, by Jane Ziegelman, Harper Perennial, 2010, pp. 183–227.

Butler, C. T. Lawrence., and Keith McHenry. Food Not Bombs (Revised Edition). See Sharp Press, 2000.

Enck-Wanzer, Darrel, editor. Young Lords: A Reader. NYU Press, 2010.

Ferguson, Sarah. “A Brief History of Grassroots Greening in NYC .” Under the Asphalt: Community Gardens in New York City, skillshares.interactivist.net/gardens/h_1.html.

“Food Waste FAQs.” US Department of Agriculture, http://www.usda.gov/foodwaste/faqs.

“‘Found in Garbage Boxes: Stuff That Is Utilized as Food for Some People.’” New York Times, 15 July 1883.

“Free Store (New York).” New Yorker, 14 Oct. 1967, p. 49.

Goldenberg, Suzanne. “The US Throws Away as Much as Half Its Food Produce.” Wired, Conde Nast, 3 June 2017, http://www.wired.com/2016/07/us-throws-away-much-half-food-produce/.

Hassell, Malve von. The Struggle for Eden: Community Gardens in New York City. Bergin & Garvey, 2002.

“History.” La Plaza Cultural De Armando Perez Community Garden, http://www.opencity.com/laplazacultural/history/.

Klejment, Anne. “‘From Union Square to Heaven.” Radical Gotham: Anarchism in New York City from Schwab’s Saloon to Occupy Wall Street, edited by Tom Goyens, University of Illinois Press, 2017, pp. 109–111.

Lobbia, J.A. “The Coqui vs. the Bulldozer.” The Village Voice, 1999, http://www.villagevoice.com/1999/11/23/the-coqui-vs-the-bulldozer/.

Martinez, Miranda J. Power at the Roots: Gentrification, Community Gardens, and the Puerto Ricans of the Lower East Side. Lexington Books, 2010.

Patterson, Clayton, “An Interview with Father George Kuhn, former pastor of St. Brigid’s Church.” Resistance: A Radical Political and Social History of the Lower East Side, edited by

Clayton Patterson, Seven Stories Press, 2007, pp 112-122.

“Research, Reports, and Financials.” Food Bank For New York City, http://www.foodbanknyc.org/research-reports/#.

Scharfenberg, David. “Coming Back to Fight for the Church of Their Ancestors.” The New York Times, 18 June 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/18/nyregion/thecity/18chur.html.

Schulz, Dana. “Remembering the Toy Tower .” Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, 17 Jan. 2012, gvshp.org/blog/2011/07/01/remembering-the-toy-tower/.

Shearman, Sarah. “In New York City’s Lower East Side, Gardening Is a Political Act of Resistance.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 11 Aug. 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/aug/11/new-york-lower-east-side-community-gardens.

Shepard, Ben. “Esperanza, Garden of Hope.” Tenant.net , http://www.tenant.net/tengroup/Metcounc/Mar00/Esperanza.html.

Wallace, Deborah, and Rodrick Wallace . “Benign Neglect and Planned Shrinkage.” Verso Books, 25 Mar. 2017, http://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3145-benign-neglect-and-planned-shrinkage.

Weinberg, Bill, “Tompkins Square Park and the Lower East Side: Legacy of Rebellion.” Resistance: A Radical Political and Social History of the Lower East Side, edited by Clayton Patterson, Seven Stories Press, 2007, pp 375-387.

Wren Awry was raised in the suburbs of NYC, but currently lives and writes in southern Arizona. Their essays have been published by Entropy, The Rumpus and in the anthology Rebellious Mourning: The Collective Work of Grief, among other venues. They curate Nourishing Resistance, an interview series about food, culture, and social change that’s hosted at Bone + All; teach food writing from an anti-capitalist lens; and work as an Education Coordinator at the University of Arizona Poetry Center, where they develop, support, and implement creative writing programs for K-12 students.The painting accompanying this essay is by Patri Hadad, More of Patri’s work can be seen at www.patrihadad.com.