April 2024

Ryan Fatica

As building occupations and encampments of public space tear across university campuses throughout the U.S., the world is once again pondering that perennial, albeit unpredictable, catalyst for social change: the student movement.

Throughout the latter half of the Twentieth Century, students leveraged their unique position in American society to contribute to social movments, from the Civil Rights Movement to the struggle to end military aggression in Southeast Asia, to the campaign to end apartheid in South Africa. In 2008, the New School occupation in New York against austerity measures in the wake of the financial crisis led directly to the student occupations throughout the University of California system in 2009. These movements set a high water mark for social movements to come, with tactical interventions later used by Occupy protesters around the country.

Missing in this timeline, though, is the history of student organizing and activism in Arizona. On April 26, 2024, students at Arizona State University launched an encampment on the Tempe campus’ front lawn, stringing up a banner marking it a “liberated zone.” When police moved in, destroying tents and arresting four protesters, students and community members linked arms and quickly regrouped, reestablishing camp. When the university turned on the sprinklers in hopes of driving out the occupiers, they placed a 5-gallon water jug, a memetic symbol of the current student movement, over the sprinkler head. Community members and students then held Friday prayers on the front lawn.

What’s emerging from this flurry of activity that combines the efforts of students, community activists, and others, is a lesson well-known to campus occupiers of the past: the campus belongs to everyone; there are no outside agitators.

The University of Arizona has been the site of a week of actions against Israeli Apartheid, and on Thursday, April 25, a group of 200-300 people marched through the campus proclaiming their solidarity with the people of Gaza.

It may be difficult, in this moment, for students at the University of Arizona to know that their efforts have a long legacy. In large part, the history of political resistance at the university has been memory-holed, leaving behind an image of a totally controlled environment in which the balance of power is firmly in the hands of the establishment. Raytheon reigns supreme and, as the first and second largest employers in Tucson, Raytheon and University of Arizona want us to believe that industry and the university have always had the city fully under their boot.

Alas, the history lives on in the archives, and in the memories of those still with us who lived through it. What follows is a brief history of a 1971 campus uprising, in which students and so-called “street-freaks” fought the police for three consecutive nights in a rowdy contestation of public space. Their message was heard loud and clear: The campus is ours if we fight for it.

As the U.S. government, via its proxy state in the Middle East, continues to wage genocide in the name of the American people, may this story lend courage to those now deciding whether to act and how far to go.

On January 21, 1971, at about 4:30 p.m., campus police at the University of Arizona in Tucson approached a group of young people gathered near the fountain in front of Old Main, demanding they disperse. The kids, according to the cops, were drinking wine. Some left, others didn’t. When cops tried to arrest those who remained, in the buttoned-up language of the Arizona Daily Star, “a scuffle ensued.”[1]

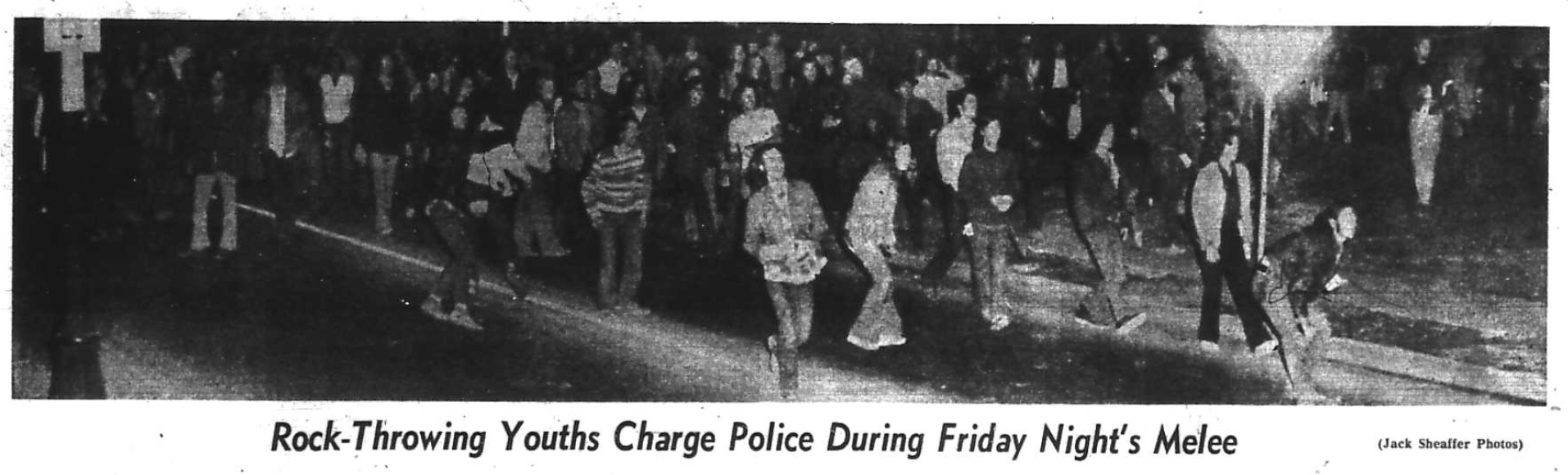

That scuffle marked a tipping point in a yearslong, simmering battle between young people in Tucson trying to live free and the forces of law and order set on reining them in. The result was three successive nights of street battles between youths and cops, centered on the western part of campus. Kids threw rocks, bricks, bottles, oranges from campus trees, and Molotov cocktails, at police who responded with predictable violence—beating them with nightsticks, firing “nausea gas” into the crowd, and ultimately dragging 143 off to languish in the even-then horrific conditions at the Pima County Jail.

“If ‘helter skelter’ was unleashed after 1970,” writes historian Mike Davis, “the Manson gang were bit players compared to the institutions of law and order.”[2] Davis was writing about the F.B.I and L.A.P.D. crackdown on the Black Panthers and the Chicano liberation movement in Los Angeles, but it’s easy to see how the bloody Manson-family-esque rampages of law and order, eager to crack down on a generation of young people trying to get free and take down the American empire in the process, spread across the country—even to sleepy Tucson.

The week before the uprising, members of the Student Libertarian Action Movement (SLAM) called for a picket outside the university’s main gate in protest of a proposed city ordinance against loitering. The ordinance, proposed by city councilman and University government professor Dr. Conrad Joyner, would criminalize the free use of public space. It was an effort in sync with establishment crackdowns across the country on counterculture youth following the tumultuous late-60s.[3]

The proposed City ordinance, which was rushed through the Council and passed in the days following the uprising, included sweeping language allowing police to charge a person with loitering for using public space in non-normative ways or just for hanging out. It criminalized use of public space for “gambling,” “begging,” or for “soliciting” another person to engage in “sexual behavior of a deviant nature.” It also privatized space on the public university, giving police the power to arrest anyone who “remains in or about a school not having any…legitimate reason for being there.” It also made it illegal to fail to provide a “reasonably credible” account of one’s activities and conduct when confronted by police.[4]

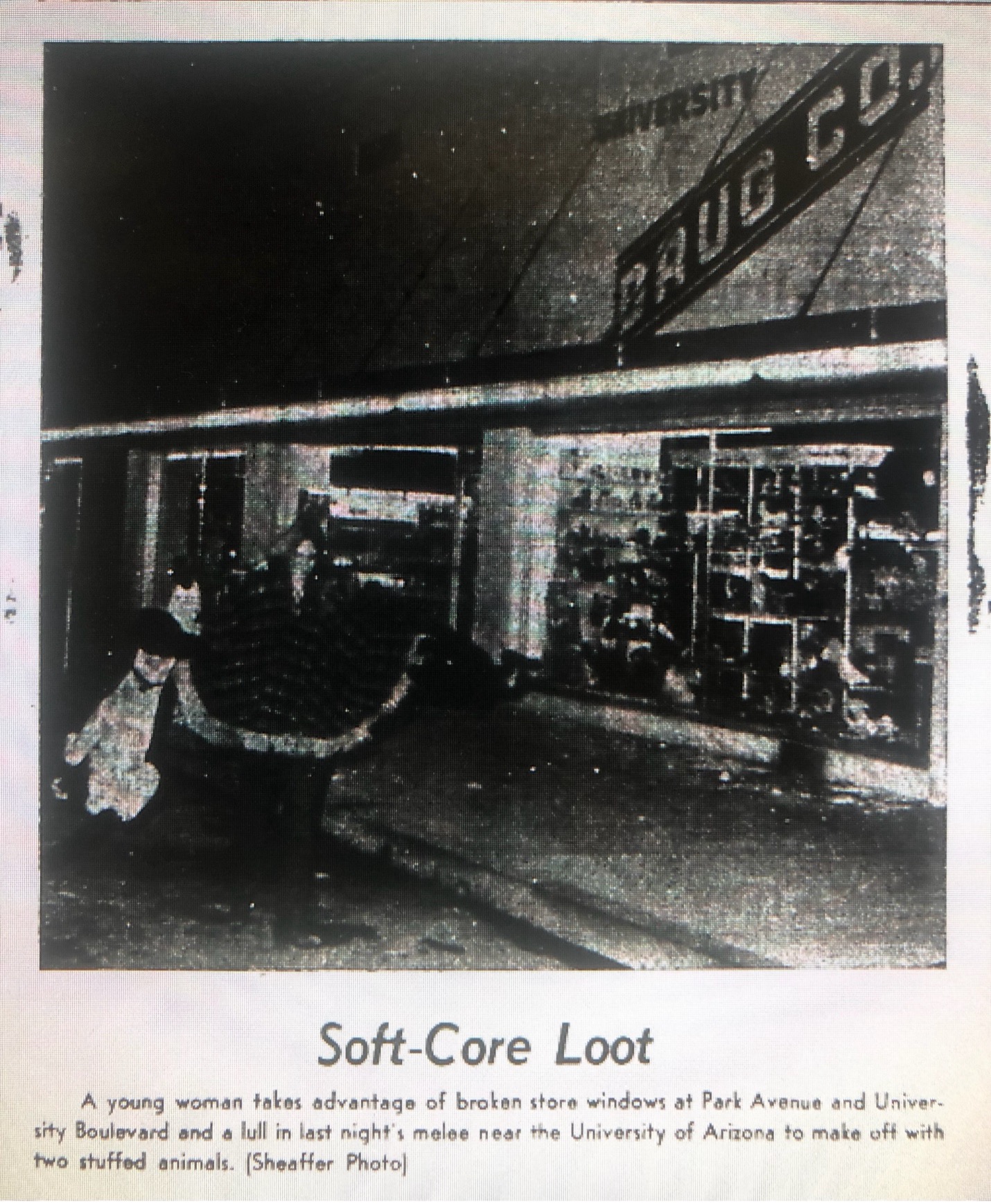

The crackdown was pushed, in part, by the owners of University Drug Co.—which occupied the northwestern corner of E. University Blvd. and N. Park Ave. next to the University’s main gate for 80 years before vacating in 2002 (the original building was later torn down and replaced by the strip mall monstrosity currently in that location).

“The conditions existing at the main gate of the campus—both on and off the campus,” wrote the owners of University Drug Co. in a notice published in the Arizona Daily Wildcat on January 14, 1971, “have made it next to impossible to keep open and subject our employees and customers to the begging, profanity, filth and intolerable atmosphere that prevails especially at those times.” Those times were after 6 p.m. in the evenings, Monday through Saturday, and all day Sunday, when the store would now be closed until further notice. “When the Authorities, both University and city, see fit to correct this condition we will reopen,” the notice concluded.[5]

The ordinance followed a similar one, previously under consideration by the City Council, banning hitchhiking–a common mode of transportation at the time among the city’s youth– within Tucson city limits.

The loitering ban would affect students, but the target was largely the “street freaks”: counterculture youth who migrated to Tucson seasonally, as they still do.

“It was hard for the Chamber of Commerce to publicize the sun, fresh air and relatively low cost of living to middle-class northerners without the same elements appealing to a more transitory crowd,” wrote Tom Miller, a Tucson-based writer. “Word on the Boston-to-Boulder-to-Berkeley street circuit went out that indeed Tucson was a most hospitable town in the winter, the dope was less expensive and more available than elsewhere and the street scene had not totally been abandoned as elsewhere.”[6]

As the law sought avenues for encircling and strangling the growing counterculture, opposition emerged from various camps—the politicized students, the hippies, and the working-class counterculture youth.

“In the event that this intended harassment advocated by Dr. Joyner and others becomes a reality,” wrote SLAM spokesperson Fred Woodworth in a statement, “SLAM will organize a campaign of civil disobedience and mass protest.” When the events of January 1971 eventually escalated beyond SLAM members’ control, Woodworth would disavow the uprising, telling reporters he didn’t agree with property destruction.

“For their part,” wrote Miller years later, “the city was used to the calm trippy good-vibes middle-class hippies. What they got in the winter of ’70-’71 was working-class dropouts who had more street savvy and survival instincts than the more traditional middle-class dropouts. On a Thursday afternoon the shit hit the airconditioner.”

Following the late afternoon police crackdown on Thursday, January 21, youths started amassing at the main gate of the University. Radio Station KTKT newscasters said on-air during a 6 p.m. broadcast, “There is something happening at the University main gate. We don’t know what it is yet.” Their language was perhaps intentionally reminiscent of a popular song by Stephen Stills celebrating an earlier youth uprising over the use of public space, the late ‘60s battles for the freedom of kids to freely use the Sunset Strip in L.A. (There’s something happening here/ What it is ain’t exactly clear”).

Shortly thereafter, the radio station began broadcasting from the scene of the amassing crowd, spreading news of the response to police violence throughout the city.[7] Hearing the news over their radios, students, radicals, hippies, and reporters rushed to the scene.

The group spread out from the main gate north along N. Park Ave. to Speedway Blvd., eventually amassing a crowd of about 500 people. Campus police called in reinforcements from the Pima County Sheriff’s Department, City police and the police tactical squad, which together amassed an army of about 400 cops.[8]

Reports in the aftermath of the ensuing melee vary, with each group blaming the other in the press for making the first move. “Hundreds of people took to the streets, seized the offensive against oncoming troopers from the city, state and county police, and in general caught the merchants and local power-structure off-guard,” wrote Miller. “Burning trash-cans rolled toward police, followed by empty coke bottles and rocks in the air.”

Windows of several businesses, including University Drug Co. were smashed out, along with the windshields of several police cruisers.[9] Pima County Sheriff Waldon V. Burr would later make the dubious claim that “several shots” were fired at police that first night. “He did not indicate who fired the shots or from where the shots came,” reported the Arizona Daily Wildcat. Contrary to many reports, as well as photographs of the event, Burr also claimed “my men haven’t had to use a billy club at all.”[10]

Others sought to put the blame on the Tucson power structure for setting off the riots. “The drugstore owner, mayor and the entire Police Department are guilty of inciting riots,” said Ricardo Malta, a so-called “street person” interviewed by the Daily Wildcat. “They make this area unsafe for our people. I’m quoting the police on this: their aim is to drive us out.”

According to the Daily Wildcat, most street people viewed the ensuing “three-night rampage” as a police riot. “Everyone was getting along fairly well before it happened,” Dan Nichol told the student newspaper, “but just a little bit of turmoil occurs, and the cops lose their cool. Then as soon as someone gets knocked over the head, total polarization sets in. The next step is overreaction, and with it, the passage of stupid and restrictive new laws.”

These voices, recorded by the student newspaper in a rare moment of decent journalism, made clear that the city’s street people, disenfranchised youth, racialized groups and political dissidents saw the ongoing war between them and the establishment as nothing less than a struggle to annihilate their way of life.

“So now the germs are longhairs, blacks and chicanos,” said another man who refused to give his name to the Wildcat. “It is the city’s aim to destroy all of us. If we are germs, let us spread a disease: revolution.”

Thursday night’s battle mostly centered around Speedway and Park, where the crowd of students and street people faced off with the city’s police force. “…police and youths alternately attacked each other and then retreated,” wrote Daily Star reporters. Police cleared the main gate area and began pushing the crowd north toward Speedway, concentrating students in one area, while campus police cleared the University grounds, approaching from the east.

Around 8:45 p.m., the youths “made several countercharges, throwing bottles and rocks and chasing the police back down Park for at least half a block. Police began using tear gas and the crowd broke into small bands.”[11] One cop told reporters that when police broke ranks and began retreating south on Park, “we got the hell beat out of us. It was the dumbest thing I ever saw.”

The crowd then broke into smaller groups, flowing throughout the city before eventually disbursing. By the end of the night, 53 had been arrested in total and several police officers had been injured by projectiles. “Just about all our men got hit with something or other,” one police lieutenant told reporters. “The most serious injury I have seen was a long gash on the arm of one of our men.”

At least one professor, Dr. John Robson, an associate professor of physics at the university, spoke out against police violence, telling reporters that police beat a young protester with the butts of their flashlights as they put him into the patrol car.

Some of those arrested were charged with unlawful assembly, while others faced charges of trespassing, rioting, burglary, aggravated assault, suspicion of willful destruction of property and “being a minor in possession of tobacco.”[12] The next day, handbills were circulated calling for students to keep up the battle with the cops and discussing tactical interventions for outpacing the enemy. They suggested the crowd break up into smaller groups and use “hit-and-run tactics” that evening. Others suggested combatants “take guerilla action” in small “affinity groups.”[13]

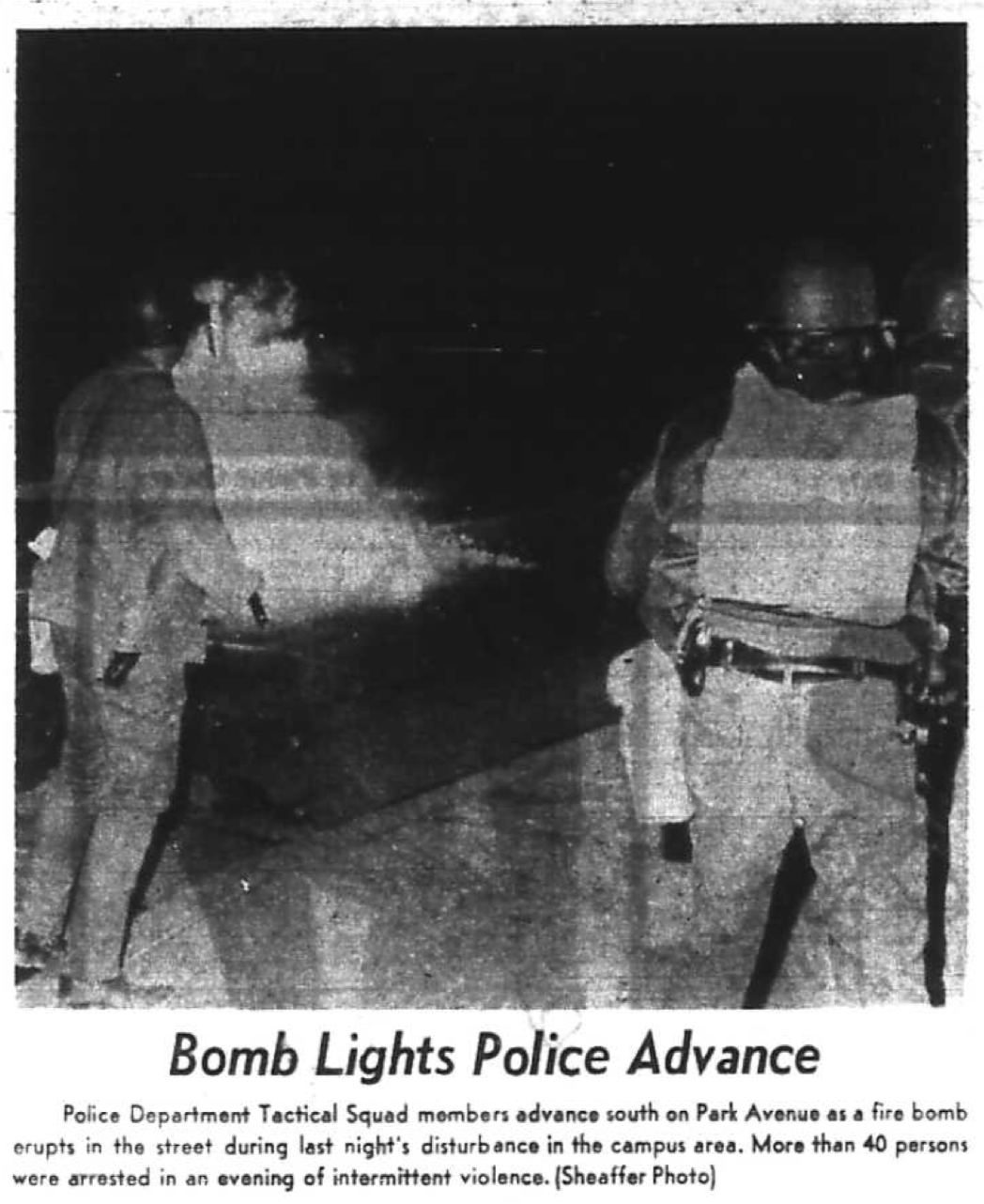

“Trash pig business stores,” one pamphlet reportedly read. “Beware of plainclothes pigs…isolate and destroy them…Don’t let anyone take your picture. Destroy all cameras…Widen battle areas: you don’t have to stay just in the University area.” As propagandists spread the word about crowd tactics, others upped their game in other ways. “Friday evening saw a repeat of Thursday night’s violence,” wrote the Wildcat, in flippant summary, “with the addition of firebombs.”

After again smashing out the windows of University Drug, rebels threw road flares and, later, “firebombs” into the building. Bystanders and do-gooders rescued the building, kicking the flares and Molotovs out into the street where they were extinguished.[14]

The tactical interventions, for their part, seem to have been successful, as Police Captain Clarence Dupnik told reporters the next day that the demonstrators were “more organized” on Friday night than they had been the previous night. “They were more difficult to handle because of their mobility.” [15]

Meanwhile, police circled the crowd in a privately owned helicopter, loaned to the police for the event. “I don’t care how many times you’ve seen it before on television,” wrote one witness. “A helicopter with a powerful torch mounted on its abdomen is an indisputably weird sight.” A year later, the Tucson Police Department would acquire its first two helicopters, providing a down-payment of $93,600 as part of a “six-month trial” beginning April 1, 1972, making Tucson the first law enforcement agency in the state to “employ two surveillance helicopters,” according to Fred Woodworth, spokesperson for SLAM and publisher of the underground newspaper The Match.

From the beginning, the helicopter was used primarily to harass and surveil Tucson’s marginalized communities, focusing on supposedly “high crime” areas. “By interesting coincidence,” Woodworth continued, “this district happens to include the homes of Tucson’s students, Blacks and Chicanos; it is well known, of course, that the poor alone commit crimes.” [16]

The problem now faced by most of Tucson’s residents—perennial harassment by circling police helicopters—apparently began almost immediately. “Oddly enough,” wrote Woodworth, “the helicopters seem to be over head almost constantly…Rarely anymore does one find oneself completely out of sight and/or sound of the State.”[17] Tucsonans formed a group to try to oppose the increase in police power, Stop the Helicopter (P.O. Box 4027, Tucson 85717), but to no avail.[17]

On Saturday evening, January 23, 1971, following two consecutive nights of rioting, the mayor and other city officials requested a meeting with “leaders” of the student and street youth groups, attempting to put down the growing insurgency with soft power. The youth presented a list of demands, including that the front lawn of the university be “turned over to them,” that amnesty be granted for all those arrested during the uprising, that there be an end to harassment of panhandlers and those using public space, and an investigation into violent policing techniques as well as the conditions at the Pima County Jail.[18]

Soft power meets “soft-core” looting as a woman flees a smashed-out storefront carrying two large stuffed animals while city leaders seek negotiations.

This latter issue continues to plague Tucson residents to this day, as community groups battle the Sheriff and county officials over the construction of a proposed new jail and death rates in the current jail are more than three times the national average.

While the “leaders” negotiated, a tense crowd formed at the university main gate.

“Now the whirley-bird skated over the people on an icicle of light and, as it went by, a volley of obscenities rose above the street,” wrote a witness of the borrowed helicopter. The crowd of about 300-400 protesters were concentrated mostly at the Standard Gas Station that once stood at the intersection of University and Park. Reporters later wrote that they’d seen youths “stuffing their pockets with rocks'' amidst the tense standoff between police and the rebels.

Meanwhile negotiations had begun to break down. Some of the youths, referred to by the Daily Star as “the street people,” walked out of the meeting around 10 p.m. when officials refused to take negotiations out of the backrooms and into the streets “to talk to the people.” The politicians wanted to smooth talk a few self-appointed leaders, not face down a popular uprising in the streets. The negotiations continued until KTKT radio station manager Phil Richardson burst in the room, to announce “this thing has blown up.”[19]

Knowing their only real bargaining chip in the situation was the continuation of property destruction and street disorder, the street kids, numbering about 400, set it off. Around 10:25 p.m., some within the crowd began throwing rocks and bottles at the amassed police. One threw a smoke bomb. The police escalated immediately, announcing that anyone in the street would be immediately arrested for rioting and shooting off “nausea gas.”

After negotiations broke down, Mayor James N. Corbett and city council moved to the police department where the Mayor signed a curfew order, effectively immediately, barring all civilian presence within a 4-mile area, including the entire university. The area stretched from Grant Ave. in the north to Broadway in the south and from Campbell Ave. in the east to 6th Ave. in the west. (Nearly fifty years later, in June 2020, the city would again announce a curfew as Tucson’s streets were once again rocked by rebellion stemming from the shockingly few gains made in issues of racial justice and police violence in the ensuing period).

One student, who dispersed through the university campus when the gas got too intense, later wrote, in inflated prose, “the cold night was a jungle of strange primates’ yelps, as if a large troop of baboons were racing through the trees from the red fires of a holocaust. The only thing really visible was the evanescent whiteness blowing gently south like a ghost barge of Medieval literature.”[20]

As in 2020, the onset of the curfew, and the resulting power of the police to arrest anyone on sight, proved too much a tactical obstacle for the students and street people to overcome, and the uprising was halted after three consecutive nights. In the ensuing weeks, the Tucson power structure would stage a revanchist program, cracking down on loitering, panhandling, hitchhiking, and other free use of public space. Students arrested during the uprisings were barred from registering for classes, and professors penned op. eds. in their defense.

Over fifty years later, the outcome of this reactionary program by university and city leaders is in full effect and the terrain of the university has shifted dramatically. As campuses across the country erupt with encampments and occupations in opposition to the ongoing genocide in Gaza, and students join with community members to link arms, fight police, and take and hold public space, it is yet to be seen whether U.A. students will embrace the legacy of 1971.

[1]“Students Battle Police,” Arizona Daily Star, January 22, 1971, 1A.

[2] Davis, Mike and John Wiener, Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the 1960s. 3.

[3] “SLAM Plans Picket Today,” Arizona Daily Wildcat, January 14, 1971.

[4] “Disorders Speed Ban on Loitering,” Arizona Daily Wildcat, January 29, 1971. 11.

[5] “Notice,” Arizona Daily Wildcat, January 14, 1971, 12.

[6] “Tom Miller Sez!”, Food Conspiracy Newsletter.

[7] “Students Battle Police,” Op. Cit., 1A.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Streetfighting Disrupts Campus Area,” Arizona Daily Wildcat, January 28, 1971, 9.

[10] Ibid., 8.

[11] “Students Battle Police,” op. cit.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Battling Brings Curfew,” The Arizona Daily Star, January 24, 1971, 2A.

[14] “Battle Renewed in Campus Area,” Arizona Daily Star, January 23, 1971.

[15] “Police Helicopters Spell Fascism,” The Match, Vol. 3, No. 10, September 1971, 4.

[16] Ibid, 8.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Battling Brings Curfew,” Op. Cit., 1A.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “ ‘Rioter’s Account of the Jan. 23 Disturbance,” Arizona Daily Wildcat, February 4, 1971, 5.